The British Régime in Wisconsin and the Northwest: Chapter 17

XVII. The Approach of War, 1809–1812

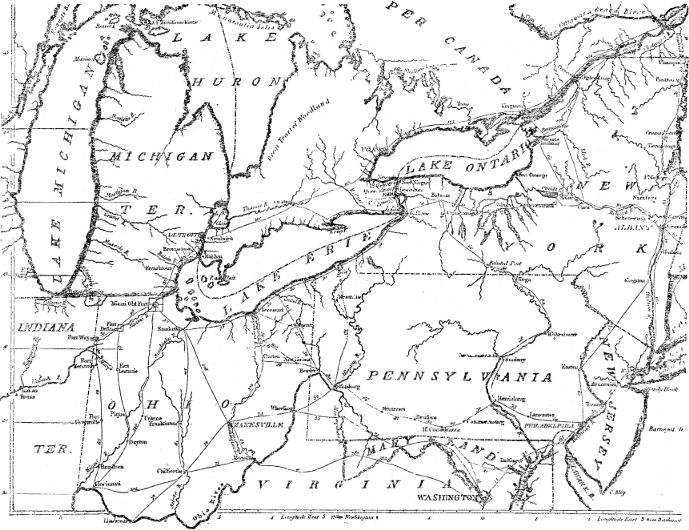

In Europe the Napoleonic wars were at their height, with the emperor winning victories on land and been maintaining with increasing difficulty its supremacy at sea. On the ocean, neutrals like the United States fared badly between the two belligerent powers engaged in their mighty struggle. In America Jefferson's pacific policy was wearing thin, and when in 1809 Madison inherited the position of chief executive the people showed a growing impatience with the non-importation and embargo laws. Jefferson's last important act had been to sign the repeal of the embargo, and on the Northwest frontier activity was renewed for the instant among the rival trading companies. The North West fur company, safe in British territory, felt very little the efforts of the United States to curb the foreign fur trade. In 1810 its partners petitioned the governor of Upper Canada to extend the road from Lake Ontario to the bottom of Georgian bay of Lake Huron in order that they might have a transport route all in British territory and not be 'exposed to the vexatious interference of the American customhouse officers.'1

The partners of the Michilimackinac company had no such resource; not only were they obliged to transport provisions and heavier articles around the lakes, subject to such accidents as the capture of their cargoes near Niagara in 1808; but they were forced by the exigencies of the trade to enter all goods through the customhouse at Mackinac and there compete with the American factory, which brought in goods without customs fees. It was even intimated that the duel between United States Indian Agent Campbell and the British trader, Crawford, had in its origin in international differences, rather than in personal enmity. 'The insolence of these foreigners,' wrote Governor Harrison of Indiana territory, 'is intolerable. They have now a great number of traders in the Indian country who have no licences and put our laws at defiance. . . . There is little doubt but that Mr. Campbell fell a sacrifice in the discharge of his duty.'2

The Michilimackinac company's returns declined so seriously in 1809 that early in the next year two of the Montreal partners visited New York in an effort to bolster up their losing concern by securing an American partnership. John Jacob Astor, the fur trade magnate of New York, refused at this time to enter into a combination with these Montreal traders. They were then forced to send to Mackinac to buy out the interests of the wintering partners.3 Their agents were George Gillespie and Toussaint Pothier who carried 'ample powers for the purchase for the whole of the Interest of the wintering Partners in the Concerns of the late Micha. Co., for for winding up the business according to the original agreement.'4 The large Montreal firms continued for one more year a combine, which was called the Montreal-Michilimackinac company, furnishing goods to the traders in the interior. Then in 1811 they succeeded in drawing Astor into their partnership and organized the South West company.

Astor, in the meanwhile, had completed his own arrangements for monopolizing the fur trade of the United States and the west coast of North America. In 1808 the New York legislature gave him a charter for the American fur company, which was to run for twenty-five years and have a capital of $2,000,000, all owned by United States citizens.5 Meanwhile, he had completed arrangements with the Russians operating on the north Pacific coast, to furnish them goods and provisions and to sell their furs in China. He had already formed a connection with the chief traders at St. Louis and aimed at founding a series of posts westward along the route of Lewis and Clark. Then in 1809 he organized the Pacific fur company.6

Astor knew he could not carry out his plans without the coöperation of the British traders, who had had experience in the fur trade. He, therefore, went to Montreal in 1809 and made overtures to prominent Scotchmen among the Nor' westers, offering them shares in his new company, which was finally organized in July, 1810. The command of the overland expedition, however, he put into the hands of Wilson P. Hunt, an American of St. Louis. The overland group including such well known traders as Duncan McDougall, Donald McKenzie, and the two Stuarts—David and Robert, left Montreal on July 5, 1810; at Mackinac they were joined by Ramsay Crooks, who was there awaiting them. August 12 they left Mackinac for Green Bay, passed over the Fox-Wisconsin route, and arrived in St. Louis the third of September. So notable an expedition had not passed through Wisconsin for many years. We cannot follow their progress to the Pacific and the fortunes there of the Astorian enterprise, but must consider the trade conditions left behind.

Astor, having sent off his western expeditions both by land and by sea, turned once more to the consideration of the trade of the interior. In 1811 he sent an agent to Mackinac to buy furs and in the same summer entered into an agreement with the Montreal firms which became the basis of the new South West company.7 This company was to be in existence for five years. Astor and the group of Montreal merchants were to share equally and to assume one-half of the profit or loss. If, however, the United States factories should be abolished, the American partner's share would be two-thirds. This furnished a powerful incentive for the American to use influence with his government to that end and this no doubt was one of the reasons that the British merchants desired Astor's partnership. The arrangement with the North West company was equally advantageous for the American; during 1811 the great Canadian concern was to retain the same limits as those arranged in 1806 with the Michilimackinac company; after that the Nor' westers would withdraw entirely from all American territory as far west as the Rocky mountains.8 West of that boundary they retained freedom for competition and ultimately absorbed Astor's Pacific fur company's enterprise.

It is quite evident that Astor in 1811 did not expect that war would break out between the United States and Great Britain, while the Montreal partners of the South West company depended on Astor's influence with his government to aid in maintaining neutrality and to obtain relaxation of the commercial restrictions that threatened the trade west from Mackinac.

President Madison continued the commercial policy of his predecessor, and the non-intercourse laws bore heavily upon the British fur traders. In 1810 the customs official at Mackinac forbade the entrance of any British goods, whereupon Robert Dickson smuggled goods worth £10,000 past Mackinac into the usual trade routes.9 The next year Dickson planned to slip through by another route; bringing in goods at Buffalo, where the collectors seem to have been lax, he took them down the Ohio and up the Mississippi to his wintering place among the Sioux. Dickson's plan succeeded, but how he outwitted the 'Yanky collectors' was a secret.10 Louis Grignon also was successful in getting his small consignment passed by the collector at Mackinac.11

The United States government feared that the British traders might be driven to extremities by the non-importation act and warned the agents at all the posts to exercise the greatest care. These agents were General William Hull, Detroit; General William Clark, St. Louis; Charles Jouett, Chicago; Erastus Granger, Buffalo; John Johnston, Fort Wayne; J. B. Varnum, Mackinac; and Nicolas Boilvin, Prairie du Chien.12 Boilvin had been transferred in 1808 to this latter place from Fort Madison upon the death of Agent Campbell. Boilvin wrote in February, 1811, to the secretary of war a long descriptive letter outlining conditions at Prairie du Chien and giving a brief history of the place. He estimated the permanent population at one hundred families, which was not far from the estimate made by Pile five years earlier. Six thousand Indians were dependent upon the supplies brought thither by Canadian traders, and so firm was the hold these traders had upon the surrounding Indians that no American traders stood any chance of success; only one American had been there the year before. Boilvin anticipated that war might begin and stated that in such an event the Indians would be wholly British in sympathy; the traders 'are constantly making large presents to the Indians,' he write, 'which the latter consider a sign of approaching war.'13

It was not only the traders but the Canadian officials themselves who made large presents to the Indians throughout the entire region of the Northwest. This practice was inherited by the British from the French régime; its temporary suspension had been one of the inciting causes of Pontiac's conspiracy; it had been renewed at Mackinac on a large scale by Robert Rogers and was continued throughout the American Revolution, the retention of the posts in the interests of the British fur trade had required a continuation of this practice of present-giving. The appetite growing with each successive visit of the tribesmen to the posts, a habit was formed which it appeared impossible to break.

The delivery of the posts to the Americans in 1796 would have been an appropriate time to discontinue the practice, but all Canada's prosperity was based on the fur trade and to have refused presents to Indians visiting British posts would have imperiled this vast interest. Moreover, England was at war and anticipated danger for her possessions in every direction. In 1797 a French invasion by way of the Mississippi was reared, and the agent at St. Joseph island wrote that it was difficult to keep the western Indians in the British interest without large distributions of presents.14 The Sauk and foxes on the Mississippi held the key to the upper river and had been favorable to the Spanish and Americans at St. Louis and in Illinois; they were, therefore, urged by British officers to visit the new post at the mouth of Detroit river, there loaded with presents and treated with great courtesy.15

In 1807 when the two nations nearly went to war over the Chesapeake-Leopard affair, an article appeared in the American newspapers stating that 2,000 Indians had visited Amherstburg and were being armed by the British and supplied with provisions and ammunition. This became an international incident, the British minister at Washington being called upon for explanations. the matter was finally submitted to Lord Castlereagh of the British cabinet, who wrote the Indians must be conciliated, for in the event of war, if not employed by the British, they would go to the help of the United States. If, however, an amicable arrangement with the United States eventuated, some joint system for the treatment of the Indians might be agreed upon and become a permanent policy.16

This statesmanlike suggestion was never acted upon, and in 1809 the requisitions for Indian presents for Upper Canada amounted to £23,793.17 Difficulties were fast approaching between the Indian tribes of the Northwest and the Americans occasioned by a remarkable movement instigated among the Shawnee, which rapidly spread in every direction. Two brothers of an obscure family of the Shawnee tribe began about 1805 an agitation against white expansion, the cession of lands to the United States, and the adoption by the red men of the customs of their white neighbors. Tecumseh, the Shooting Star, was a remarkable Indian who, like Pontiac fifty years earlier, conceived the idea that an Indian confederacy might be formed which could drive the white men beyond the Ohio, and retain for the Indians their landed heritage in the old Northwest. Tecumseh was seconded in his efforts by his brother, the Prophet, who preached a new religion that discarded all the customs adopted from whites.18 A British official wrote in 1807 from Fort St. Joseph: 'All the Ottawas from l'Arbre au Croche adhere strictly to the Shawney Prophet's advice they do not ear hats [as the white men do], Drink or Conjure, they intend all to Visit him this Autumn. . . . Whisky & Rum is a Drug, the Indians do not purchase One Galln. per month. I saw upwards of 60 of them at one time together spirits, rum & whisky were offered for nothing to them if they would rink but they refused with disdain.'19

The new religion spread rapidly among the Wisconsin tribes. The Winnebago especially were deeply influenced by the Prophet's message.20 Their chief, Caramaunee, was one of Tecumseh's principal followers, and the Prophet's army was greatly reinforced by Winnebago and also by the Rock river Sauk.21 The Chippewa joined the crusade in considerable numbers; in 1808 a fur trade post on Lac Court Oreilles was plundered by adherents of the new religion,22 and in 1810 traders in central Wisconsin suffered because the Indians refused to supply them with meat.23 The influence among the Wisconsin tribes of these Shawnee conspirators lasted for many years. As late as 1888 a Winnebago reported that he believed that Tecumseh was invulnerable and could not be hurt with a bullet.24

A large band of the Potawatomi was induced to embrace this new religion. Main Poque, chief of the Illinois river band of that tribe, was an adherent, as well as Shaubena of the Kankakee,25 and Blackbird of the Milwaukee village, son of the chief of that name of Revolutionary times. The Prophet and Tecumseh first gathered their adherents at Greenville, Ohio, where ten years earlier the great treaty with all the northwestern tribes had occurred. The signers of this treaty were now growing older, the younger warriors had forgotten their fear of the Big Knives, and the new religion made them insolent and bold. The surrounding settlers were plundered, and upon their complaints Governor Harrison ordered the Shawnee to break up this illicit settlement. In 1808 the Prophet and his followers removed to the upper Wabash, at the mouth of Tippecanoe creek. There they built up an Indian town which was estimated in 1810 to comprise 3,000 warriors.26 The Prophet's policy encouraged agricultural development, and Harrison write that 'his followers drink no whiskey and are no longer ashamed to cultivate the earth.'27

In 1808 the British at Malden sent messengers to invite Tecumseh and the Prophet to pay them a visit. At this council the British asked the Shawnee to be quiet until they heard from them; but in 1810 they came again and were furnished with a large amount of presents, even though the Indian agent wrote to his superior that he believed an Indian war was imminent. Six thousand Indians were fitted out at Amherstburg that autumn,28 and General Isaac Brock wrote: 'Our cold attempt to dissuade this much injured people from engaging in such a rash enterprise could hardly be expected to prevail, particularly after giving such manifest indications of a contrary sentiment by the liberal quantities of military stores with which they were dismissed.'29 Tecumseh told his British friends; 'I intend proceeding towards the Mid Day, and expect before next Autumn and before I visit you again that the business will be done.'30 He then set forth on his visits to distant tribes to persuade them to embrace his proposals and to unite in a vast confederacy to expel the Whites from the Northwest territory.

It is uncertain whether Tecumseh in person visited eastern Wisconsin at this time. A persistent tradition represents his interview with the Menominee chief, Tomah, who at the council in a dignified and impressive manner declined to enter into Tecumseh's conspiracy and raising his hands exclaimed: 'It is my boast that these hands are unstained by human blood.'31 A prominent Green Bay trader, however, was certain that Tecumseh did not come in person to that vicinity.32 Undoubtedly his messengers were among all the Wisconsin tribes, and Tecumseh is known to have passed along the Mississippi and to have rallied the Winnebago and Sauk of that region.33

As the Indians influenced by Tecumseh began to collect in large numbers on the upper Wabash, Governor Harrison considered this aggregation a serious menace to the frontier and his uneasiness was enhanced when in the early summer of 1809 the Prophet appeared with a considerable escort at Harrison's home at Vincennes. Although this chief professed his allegiance to the United States, the governor was not deceived by his protestations, and wrote the secretary of war that he was convinced that a conspiracy was on foot; however, a truce was made for the time being.34 That same autumn Harrison in accordance with instructions from Washington called a council at Fort Wayne of Miami, Wea, and Delawares and purchased a large additional body of land in the center of the present state of Indiana. Tecumseh expressed great indignation at this treaty for, although the new purchase did not belong to the Shawnee, he had formulated the theory that all Indian lands were the property of the tribes in common and should not be ceded except with the consent of every tribe.

In the summer of 1810 Tecumseh visited Harrison at 'Grouseland' his Vincennes estate and protested that he would never submit to the treaty of Fort Wayne, would kill the chiefs who had made the treaty, and would not permit the occupation of the land by the whites. It was at this conference that in the course of his speech he made such hostile gestures that caused Harrison's guard to think he intended to kill the governor. Tecumseh apologized the next day at the council, and Harrison wrote the secretary of war that a truce had been arranged and that he thought hostilities would not be immediate. On this occasion a Kickapoo, a Potawatomi, an Ottawa, and a Winnebago chief spoke and declared that their tribes would support the principles Tecumseh laid down.35

The next July the Shawnee chief came again with a large train of followers, who gave him 'as implicit obedience and respect as if he had been,' wrote Harrison, 'Emperor of Mexico.' He was on his way South and told Harrison of his intention to bring all the Chickasaw, Cherokee, and Creeks into his confederacy. Harrison considered that his absence would afford a favorable opportunity to break up the large gathering of Tecumseh's followers and prepared for a march on the Prophet's town.

He reached the vicinity of Tippecanoe town early in November and sent out a request for a parley; at first the Indians intended to meet the governor in a conference, and it was rumored that a Winnebago warrior had agreed to devote himself to the assassination of the governor during or after the conference, then it was thought the Americans could be easily defeated.37 This conference failed to materialize, however, and Harrison was saved from an utimely death. Early on the morning of the seventh the Indians attacked Harrison's force and after severe fighting were repulsed. Sixty Winnebago, the tribe which was credited with bringing on the conflict, were said to have been slain in this battle; the British, however, reported that only twenty-five Indians in all were killed, probably an underestimate.38

Harrison's loss was considerable, especially among the Kentucky volunteers, whose leader Colonel Joseph Daviess was killed at the first onslaught. The battle, considered a drawn conflict, was later magnified by the Americans into a victory. The British authorities immediately forwarded papers to Washington showing that their advice to the Indians had been to keep the peace. The battle of Tippecanoe decided nothing, except that the enmity of the Indians for the Americans was inveterate. Although the Prophet's town was burned and the crowd of his followers scattered, they carried, like burning brands, the fire of their hatred and their hostile intent throughout the entire West.39

This was soon evident in Wisconsin, Illinois, and Missouri, especially along the Mississippi as far north as Prairie du Chien. Governor Howard of Missouri territory and Governor Ninian Edwards of the newly erected Illinois territory, which since 1809 included the present Wisconsin, prepared for an extensive Indian war. Rangers were enrolled in both territories, those of Missouri being commanded by Nathan Boone, son of the famous Daniel. The Winnebago Indians were the most threatening. After dispersing from Prophetstown they sought to kill every American they met in revenge for their losses in the battle of Tippecanoe. A large number of these tribesmen gathered at Milwaukee, and the garrison officers at Chicago wrote that they breathed nothing but war and revenge. They also had a rendezvous on Rock river, and every boat going down the Mississippi was watched for American traders.40 All the white settlers along the border built small log forts and retired into them on the least alarm. Governor Edwards wrote February 15, 1812, that 'Indian hostilities are no longer a matter of conjecture.'41

The United States outpost on the upper Mississippi, called Fort Madison, was held by a mere handful of troops and was in a practical state of siege from January, 1812. Early in that month an English trader, George Hunt and his interpreter, Edward Lagoterie, came down from the mines above on the river, stating that on the seventh a party of twenty Winnebago appeared, killed two Americans and allowed Hunt to escape because he was known to be British.42 The Sauk Indians joined in these hostilities; they prepared for three raids, 'one to the mining country; one to Prairie du Chien; and another to Fort Madison.' One band of this tribe, favorable to the Americans, removed to the Missouri river, where, however, they terrified the frontier inhabitants by their hostile attitude and it was claimed murdered two or more frontiersmen.43

All during the winter of 1811–12 Prairie du Chien was in a state of great excitement. It was reported in January, 1812, that all but two Americans had fled from that place, some escaping amidst great danger. One of those who arrived at St. Louis in the early spring was Major George Wilson of Kentucky who had been trading at the Prairie during the winter. With him came Captain Nathaniel Pryor, of the Fort Madison garrison. Pryor had crossed the continent with Lewis and Clark and now had reentered the army, and was stationed at this remote post. He reported that two soldiers had been killed at Fort Madison, and that the Winnebago, collected on Rock river, were examining every boat for Americans while the British and French-Canadians were allowed to pass without difficulty, 'thus the Indians following the example of Great Britain, contend for the right of search.' All American goods were plundered, and the traders captured when not slain.44

Meanwhile, a number of the former hostiles visited Harrison at Vincennes, among them Caramaunee of the Winnebago, who after some parleying agreed to inform his tribe that the tomahawk was buried and to persuade them to cease hostilities. He went so far as to promise that one or two of his chiefs should go to Washington and visit the president.45 General William Clark, superintendent of Indian affairs at St. Louis, left for Washington early in 1812 with a delegation of Osage chiefs, and at the same time Boilvin conducted a group of Sioux, Iowa, and Winnebago on the same errand. The Americans of the frontier thought that this visit was merely a ruse to gain time; they reported that even while the Winnebago chiefs were on their way to the capital their warriors on Rock river numbered eight hundred, all ready to fall upon the border settlements.46

The Potawatomi on the Illinois river were also much disaffected; among them were two bands; one headed by the Main Poque wholly British in sympathy who furnished many warriors for Tecumseh's forces. The other band was opposed to the first, and Gomo its chief was spurned from the council at Malden and dubbed in contemptuous tones 'The American.' Before Clark left for Washington city, he appointed Thomas Forsyth Indian agent for the Illinois river Potawatomi and sent him to reside at Peoria. Forsyth was a half-brother of John Kinzie, trader at Fort Dearborn, and the firm of Kinzie and Forsyth was well and favorably known among the Potawatomi.47 Meanwhile, Gomo visited Governor Edwards of Illinois territory and protested his affection for the Americans, but Edwards wrote to Harrison that he thought little dependence could be placed on his professions.48

Reports of Indian outrages continued to come in from many parts of Indiana, Illinois, and Missouri. In April two men were murdered on the south branch of Chicago river, and two others escaped to Fort Dearborn. On this alarm all the outlying settlers flocked to the fort and preparations were made for defense.49 The murderers were thought to be Winnebago who went thence to join the Prophet on the Wabash. In May, Harrison reported that the Prophet had returned to his despoiled village and had three hundred Winnebago and two hundred warriors of other tribes with him.50 Tecumseh was planting corn, getting lead and ammunition from the British, and preparing for a new effort to drive the Americans beyond the Ohio. Boilvin returning from Washington with the chiefs wrote from Pittsburgh that he dared not descend the Ohio river without a guard of soldiers.

In Missouri a massacre occurred in May at the Gilbert Lick settlement one hundred miles above St. Louis, when all the neighboring settlements forted and rangers Were enlisted for an Indian War.51 In view of the threatening aspect of Indian affairs, and the widespread area of the hostile attacks it seemed that an Indian War of considerable dimensions threatened to burst over the American frontiers from the Wabash to the Mississippi. It was believed by the territorial officials that this warlike attitude was encouraged not only by the English officers at Malden but by the British traders at Prairie du Chien. Boilvin thought if an American trading factory had been placed there, it might have counteracted British influence; as it was, not an American dared remain at that place. The winter of 181112 had been especially severe, and the tribesmen were dying of famine on the upper Mississippi. The South West company traders, headed by Robert Dickson, were obliged to furnish provisions and ammunition to their customers to keep them alive. Dickson was said to have used fifteen hundred dollars worth of goods in this humane effort.52

When he arrived at Prairie du Chien some time in April, 1812, he consulted with his partners, James Aird, Joseph Rolette, John Lawe, and others, and decided in the threatening state of affairs to obtain an escort of Indians to Mackinac. Arrived at the portage early in May, he found messengers sent out by General Isaac Brock, governor and military chief of Upper Canada. Brock's messenger was François Reaume, who had come overland from Malden.53 As he passed through Chicago, Captain Heald, commander of Fort Dearborn, suspected his errand, but as Reaume hid the incriminating letter in his moccasins, Heald had no proof of his suspicions and allowed the Canadian to proceed.

Dickson immediately saw the gravity of the situation, which Brock reported to him. The British consul general at New York had warned the authorities in Canada of the near approach of war, stating that it would begin by July if not sooner.54 Had Heald or any American officer arrested this messenger to Dickson, the Wisconsin Indians would not have been at Fort St. Joseph when the actual news of war was declared. For immediately upon receiving Brock's message, Dickson began enrolling Indians as auxiliary troops.55 From Green Bay he sent a party of Sioux, Winnebago, and Menominee to Amherstburg, while he himself with one hundred and thirty of the same tribes reached Fort St. Joseph by the first of July.56

Thus was the war, which threatened between the Indians and the American frontiersmen, merged in the greater conflict between the two nations—Great Britain and the United States. The West was a unit in desiring such a war, notwithstanding its fear that most of the savages would act with their enemies. The president's proclamation June 18, 1812, that a state of war existed was slow in reaching the garrisons around the Great Lakes at Mackinac, Detroit, and Chicago. The British, beforehand with their preparations, secured the initial advantage.

1 Mich. Pion and Hist. Colls., xxv, 273–275.

2 Messages and Letters of Harrison, i, 312.

3 Tohill, 'Robert Dickson,' 36.

4 Forsyth, Richardson and company to Jacques Porlier, Montreal, June 10, 1810, in Wis. Hist. Colls., xix, 337–338.

5 Kenneth W. Porter, John Jacob Astor, Business Man (Harvard Studies, Cambridge, 1931), i, 165.

6 Washington Irving, Astoria (New York, 1897) is the standard reference; see also Porter, Astor, i, passim.

7 Porter, Astor, i, 253.

8 Ibid., 461–469.

9 Wis. Hist. Colls., ix, 178–179.

10 Ibid., xix, 342; Askin Papers, ii, 696.

11 Wis. Hist. Colls., xix, 340.

12 Ibid., 338–339.

13 Ibid., xi, 247–253.

14 Mich. Pion. and Hist. Colls., xxv, 136.

15 Ibid., xv, 48; xxv, 186.

16 Ibid., xxiii, 69; xxv, 238, 259.

17 Ibid., xxiii, 70–72.

18 Galloway, Old Chillicothe, 106–120, 128–134, 147–152.

19 Wis. Hist. Colls., xix, 322.

20 Life of Black Hawk, op. cit., 31.

21 Wis. Hist. Colls., xx, 267; Draper MSS, 1YY27, 38–39.

22 Wis. Hist. Colls., xix, 168, 207.

23 Ibid., iii, 268.

24 Ibid., xiii, 459.

25 Ibid., vii, 415–416.

26 Messages and Letters of Harrison, i, 425.

27 Ibid., 296.

28 Mich. Pion. and Hist. Colls., xxv, 275–277.

29 Lady Matilda Edgar, General Brock (Toronto, 1904), 151.

30 Mich. Pion. and Hist. Colls., xxv, 276.

31 Wis. Hist. Colls., i, 53–54.

32 Ibid., iii, 268; see on this subject, ibid., vii, 411.

33 Ibid., xi, 221; xiii, 451; xx, 267; Messages and Letters of Harrison, i, 427.

34 Messages and Letters of Harrison, i, 349–350.

35 Ibid., 459–469; Draper MSS, 25S91. Soon after this it was reported that the Winnebago had killed eleven of the confederates, and that the Prophet's band was breaking up. Draper MSS, 25S95.

36 Messages and Letters of Harrison, i, 542–551.

37 Draper MSS, 266S31.

38 Wis. Hist. Colls., v, 142; Mich. Pion. and Hist. Colls., xv, 66; Draper MSS, 7U86.

39 Mich. Pion. and Hist. Colls., xxv, 291–292.

40 Draper MSS (citations from Louisiana Gazette of St. Louis) 26S32–35; Iowa Journ. of Hist. and Pol., 1913, 517–540.

41 American State Papers: Indian Affairs, i, 808.

42 Ibid., i, 805; Draper MSS, 26S31–32; Niles' Register, ii, 5.

43 Life of Black, Hawk, op. cit., 31; Draper MSS, 23S116–117.

44 Draper MSS, 26S38–39; letter of Nicolas Boilvin, January 12, 1812, United States department of war, 'old records.'

45 Niles' Register, ii, 69.

46 Draper MSS, 26S42, 46; Mich. Pion. and Hist. Colls., xv, 196–197; letters of Boilvin, July 12, 1812, September 19, 1812.

47 Wis. Hist. Colls., vi, 188.

48 Illinois state historical society Transactions, 1904, 101–112.

49 Quaife, Chicago and the Old Northwest, 211–214; Juliette A. Kinzie, Wau-Bun (Menasha, Wis., 1930), 157–158; Draper MSS, 26S47–50.

50 Messages and Letters of Harrison, ii, 49, 58.

51 Wis. Hist. Colls., ii, 204.

52 Draper MSS, 26S51–52.

53 Ninian W. Edwards, Life and Times of Ninian Edwards (Springfield, 1870), 324, 333. The name as given in this document is 'Keneaum,' doubtless a misprint for 'Reheaum,' as the name was often spelled, see also Mich. Pion. and Hist. Colls., xv, 180–182.

54 Lady Edgar, General Brock, 202.

55 Wis. Hist. Colls., xii, 139–140.

56 Ibid., 140–141; Mich. Pion. and Hist. Colls., xv, 194–195.

![Homepage [Logo]](/images/logo.png)

![[Public Domain mark]](http://i.creativecommons.org/p/mark/1.0/88x31.png)