War 1812 by George S. May: Chapter 1

I

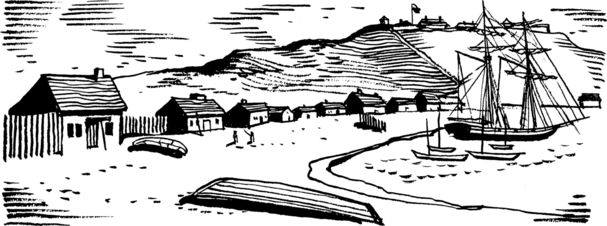

It was midsummer, 1812, normally the busiest time of the year on Mackinac Island—a time when the little island in the Straits between Lakes Michigan and Huron hummed with activity. But 1812 was not a normal year. For some time now the United States and Great Britain had been locked in an earlier version of the Cold War which reached a climax in 1811 when the Americans banned the importation of British goods. In the Great Lakes region this embargo had crippled the fur trade, upon which Mackinac Island's prosperity depended.. A quietness descended over the island such as it had not known since the British three decades before had transformed a place where a few Indians fished into the commercial and military headquarters of a vast wilderness empire.

In some ways the island has changed greatly since 1812, in other ways it has not Then as now the village's main street hugged the shore along the southern edge of the island, with a second street running behind it in the western end of the town. With the exception of one or two buildings such as the government factory, established by the United States in an effort to break the British fur-trade monopoly, the houses were humble, one-story log huts, roofed with bark. Nearly every yard had its garden, enclosed by cedar picket fences which reached almost to the eaves of the houses. With virtually no vehicles on the island to keep them down, the weeds grew in luxurious profusion on either side of a narrow path d'own the middle of the streets. Even then, though, a visit to' Arch Rock or Sugar Loaf or Robinson's Folly was enjoyed by all who came to the island, and the fort up on the hill, with its three white blockhouses, its ramparts pierced by the South Sally Port, and the stone quarters in which the officers lived had the same features that have always distinguished it.

Although 1812 was a bad year for the fur business, even this year there were a few vessels in the harbor in July and others, loaded with furs and pelts, were due in from Chicago momentarily. Some fur traders and French-Canadian voyageurs, too, had arrived to conduct their business and enjoy this brief contact with the civilized world. Indian men and their families drifted in and out, for this was the season when they received from the white men the presents upon which they had become so dependent.

The Indians' attitude this summer puzzled the young commander of the fort, Lieutenant Porter Hanks. Until recently they had been friendly, but now some of the Ottawa and Chippewa chiefs had grown almost hostile to the Americans. Then there were the reports of large numbers of Indians gathering at the British post on St. Joseph Island, forty-five miles to the east, to plan an attack on Mackinac Island. Finally Hanks talked with leading American citizens on the island, and the decision was made to send "a confidential person" to keep a watch on the St. Joseph situation.

The date was July 16, 1812. The Americans were blissfully unaware that the United States had been at war with Britain since June 18. Now time was running out. In a few hours the war would engulf Mackinac Island, and within a month Porter Hanks would be dead.

To veterans of World Wars I and II or the Korean War, the War of 1812 must seem to have been a strange, even silly conflict. What else can one think of a war whose name ignores the fact that heavy fighting continued for more than two years after 1812; a war in which the most famous American victory on land occurred after the peace treaty had been signed; a war that was remarkable because of its whopping number of bungling leaders and ill-trained troops with an itch to run at the first sound of battle.

But hilarious as some of its incidents were, the War of 1812 was no laughing matter. Victory or defeat was of crucial importance to the young American republic's development. The peace of 1814 left the boundaries between Canada and the United States back where they had been before the war, thwarting American hopes of expanding northward, but also crushing the British dream of regaining Michigan and other parts of what is now the Middle West.

The War of 1812 is the only war since the United States became a nation in which fighting has raged on Michigan's soil. One of the main areas of conflict in Michigan and the entire Great Lakes was Mackinac Island, which fell into British hands at the start of the war and from which the British were able to control a vast area from Georgian Bay, Canada, on the east, to Prairie du Chien on the Mississippi River, far to the southwest.

Michilimackinac Island, as it was still called in those days, was familiar ground to the British who had built Fort Michilimackinac there in 1779-81. Because of the island's importance in the fur trade, they had held on to it until 1796, thirteen years after the treaty ending the American Revolution had turned the area over to the United States. When they finally withdrew, the British built a fort on St. Joseph Island, just inside Canadian waters at the south end of the St. Mary's River. Here the Indians came to receive presents, but many fur traders continued to prefer Michilimackinac as their headquarters, rather than St. Joseph's, as the new post was usually called.

During the winter of 1811-12, as war clouds gathered, the British in Canada charted the course of action they would follow if war came. In the northern Great Lakes they would first capture Fort Michilimackinac in order to protect the fur-trade routes to the west and to Lake Superior, and also to win the allegiance of the Indians of the Great Lakes.

An attack on Fort Michilimackinac would have to come from St Joseph's, and this is where the whole plan seemed likely to break down. The British garrison in 1812 consisted of a sergeant and two gunners of the Royal Artillery and forty-four officers and men of the 10th Royal Veteran Battalion. As events were soon to prove, the fort's commander, Captain Charles Roberts, was an outstanding military leader. Indeed, Roberts served his country as well as did a later member of the same family, Lord Roberts, British military hero of the Boer War. In 1812, however, Captain Roberts was a question mark a twenty-year veteran with the British army in India and Ceylon, who in September, 1811, had been transferred to the opposite end of the empire—to St. Joseph's, where he had to deal with totally different conditions and peoples from those his training in the East had taught him to handle.

But then a captain is no better than his men, and Captain Roberts' men were a sad lot. The Veteran Battalion consisted of old soldiers who were considered good for little else but garrison duty. Roberts, who was himself seriously handicapped by poor health, described his men as willing to obey orders but "so debilitated and worn down by unconquerable drunkenness that neither the fear of punishment, the love of fame or the honor of their Country can animate them to extraordinary exertions." Nor was the fort any more impressive than its garrison. It consisted of a blockhouse and several buildings enclosed by a picket fence, all in wretched repair, and several antique guns which presented almost as great a threat to the lives of their gunners as they did to the enemy. The fort, in short, was incapable of withstanding an attack.

Lieutenant Hanks, with sixty-one men lodged in the sturdier Fort Michilimackinac, on an island sometimes compared with Gibraltar, apparently had little cause to be alarmed by an attack from St. Joseph's. Actually, however, his position in the event of war was virtually hopeless. He and his men were alone in a hostile wilderness, where the great majority of inhabitants were British sympathizers and where the nearest American outposts were hundreds of miles to the south at Detroit and Chicago. The United States had no navy on the upper Great Lakes. If war came, control of the lakes would go to the British by default, and Mackinac Island would be cut off from supplies and reinforcements.

Months before war was declared, the British were busily lining up additional forces to back up their garrison at St. Joseph's. They received assurances of support from the North West and Michilimackinac fur companies. In a short time, company officials promised, they could place at Roberts' disposal canoes, armed vessels, and hundreds of English and Canadian employees, toughened by years of exposure to the dangers and rigors of northern Canada and the American west.

But the decisive factor in the war in the upper Great Lakes would be the ability of the British to call in large numbers of Indian warriors to aid them. Two men, John Askin, Jr., and Robert Dickson, did more than any others to keep the Indians in the British camp. Askin had been born fifty years earlier at L'Arbre Croche on Michigan's lower peninsula. For the past five years he had been Indian interpreter at St Joseph.' s. From his father, a famous fur trader, Askin had inherited a name that was known and respected throughout the Great Lakes. His mother was an Ottawa Indian. Because of this background, Askin was of great assistance to the British commanders at Michilimackinac, keeping some of the Indians from the nearby area constantly at hand throughout the war, in addition to organizing and supplying the hundreds of warriors who came to the island each summer to assist the British here or on other fronts.

The services of Robert Dickson, although perhaps no more valuable than Askin's, were far more spectacular. This redhaired, 47-year-old Scotsman, a big six-footer, was himself one of that spectacular breed of men who always seemed to be attracted to the frontier. Coming out to Canada from Scotland in the 1780's, Dickson entered the fur trade at Michilimackinac. His trading took him west, and he became the best-known trader in the Upper Mississippi Valley. By 1812 there were few parts of what is now Wisconsin, Minnesota, the Dakotas, and Iowa that he had not explored. Along the way he had acquired immense influence over the western Indian tribes, partly as a result of his marriage to a Sioux woman, To-to-win, sister of Chief Red Thunder, and partly because of his warm-hearted interest in the welfare of these peoples.

In February, 1812, General Isaac Brock, brilliant British commander in Upper Canada, sent a secret memorandum to Dickson, who was in the west looking after his business interests and helping the Indians who were suffering from lack of food and an unusually hard winter. Brock wasted no words. Should war come, he asked Dickson, how much help could "you and your friends" give to the British and how soon could this assistance be expected' Four months later, Brock's two Indian couriers found Dickson in Wisconsin, on his way to St. Joseph's. Mascotapah, or the Red-haired Man, as the Indians called him, scanned Brock's message and dashed off a reply, assuring Brock that the western Indians were eager to help the British. He confidently promised to round up as many of his "friends" as possible and come with them to St. Joseph's by June 30, only twelve days from the time he wrote. Dickson kept his promise, reporting to Captain

Roberts punctually on the thirtieth with 130 Sioux, Winnebago, and Menominee warriors.

No one yet knew that war had broken out. Four days after Dickson arrived at St. Joseph's, however, Toussaint Pothier, agent for a fur company in which the American, John Jacob Astor, was a partner, came in from. the east with word that the United States had declared war two weeks before. Astor, who happened to be near Washington at that time, had immediately sent off messages to St. Joseph's in a:frantic effort to safeguard the trade goods he had stored there before news of the war reached that area through official channels. Pothier, one of Astor's messengers, was a loyal British subject who naturally told his news to Roberts and other British officials.

On July 8, Roberts was officially notified by Brock that the war was on and that he should act accordingly. The captain, a real professional, sprang into action, vigorously and decisively. He requisitioned guns and supplies from the storehouse of Pothier's company, and commandeered the North West Company's 70-ton armed schooner, the Caledonia, which happened to be passing by. He organized about 150 voyageurs from St. Joseph's and Sault Ste. Marie into a battalion led by the fur trader, Lewis Crawford, and assisted by Pothier, John Johnston of the Soo, and other traders. The trading post at Fort Williams, far 'across Lake Superior, was requested to send as many men as were available there. Finally, Roberts directed Dickson to comply with his orders and added about 280 Ottawas and Chippewas, led by John Askin, Jr., to Dickson's band of western Indians whose fierce desire to fight the Americans helped buoy the spirits of the others.

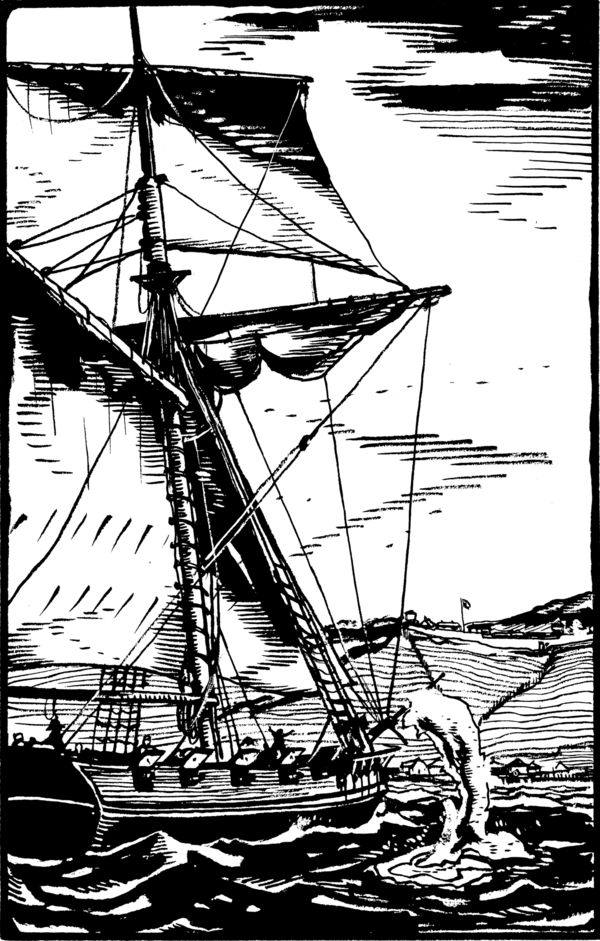

Brock followed his first dispatch in four days with a second, telling Roberts to take no more actions until he received further orders. The captain could not wait long, however, for the Indians were impatient to take to the war path. He breathed a sigh of relief when orders came from Brock on July 15 to do whatever he deemed necessary. Without hesitation, Roberts decided to attack Fort Michilimackinac immediately. "I embarked on the morning of the 16th with two of the six-pounders and every man I could muster," he reported, "and at Ten o'clock the signal being made we were under weigh."

It was a strange and frightening sight Roberts and the other leaders on board the Caledonia, the colorfully-attired Canadians and red-coated soldiers in the voyageurs' batteaux, and, everywhere, canoes filled with yelling, painted Indians.

Late the same day, Michael Housman set out in his own canoe from Michilimackinac. A strong-willed Pennsylvanian who had been engaged in the fur trade for about twenty years, Housman had been selected by Hanks as the "confidential person" to go to St. Joseph's because he had legitimate business on that island and thus would not be suspected of spying.

Housman and his canoeman glided silently through the darkness of the northern Michigan summer night. Suddenly, after they had gone only fifteen miles, they ran right into the British flotilla. Quickly Housman was taken prisoner and brought before Captain Roberts. Although Housman was a captain in the Michigan militia, he did not prove to be a difficult prisoner. He was, after all, not among strangers. Dickson, Pothier, Askin, Crawford, and Johnston were all old acquaintances. In a short time, Roberts knew the weaknesses of the American garrison and knew also that its members were unaware that a state of war existed. Not wishing to expose the civilian population of Michilimackinac to the uncontrolled wrath of the Indians, Roberts told Housman that he would release him when they reached the island so that he might tell the people to take cover in the distillery under the bluff west of the village, where a British guard would be sent to protect them. In return, Captain Housman promised not to inform the American garrison that the British were coming.

At 3 a.m. on the morning of July 17, the British landed at a cove on the northwest shore of the island, where Housman had a farm. The fort and the village were about two miles south of this point, which ever since has been called British Landing. While Housman hurried away to the village, Roberts, Dickson and Askin, both dressed and painted like the Indians they led, Pothier, Crawford, and the other leaders urged their men through the woods towards Roberts' objective, which was the high ground that rises well over a hundred feet immediately to the rear of the fort, Thirty years before, a British officer sent to inspect the newly-built fort had noted in amazement that it was completely vulnerable to attack from this height. "From this place the Fort is so effectually commanded that it never could resist cannon from hence," he declared, "as the Garrison would not dare to shew themselves in their works." Now Roberts planned to do just that. Bringing his two six-pound artillery pieces ashore, he entrusted to his Canadians, who were used to portaging heavy boats long distances overland, the job of dragging one of these unwieldy guns to the top of this height.

While this activity was going on, Housman was in the village, going from door to door awakening his fellow-villagers and directing them to go to the distillery at once. Many of the islanders were glad that the British were back on the island again, but, knowing that if fighting broke out the Indians would not care whom they killed, the local citizens hastened to take advantage of the protection that Roberts offered them.

Housman scrupulously kept his promise not to tell Lieutenant Hanks what was happening. However, the fort's surgeon's mate, Dr. Sylvester Day, who lived in the village, came scrambling up the hill to the fort around daybreak and breathlessly told the American commander what was happening. In later years, an oldtimer recalled that Hanks sent Lieutenant Archibald Darragh into town to learn exactly what was going on. Darragh walked through the deserted streets to the distillery, where he talked briefly to some of the people gathered there. As he turned to leave, the British guard tried to stop him, but Darragh and the two men with him drew their pistols and walked slowly backwards until they reached a safe distance and then turned and ran to report to Hanks.

Lieutenant Hanks made every preparation he could to meet an attack, calling out all of his men, fifty-seven, who were fit for duty that morning. But as he looked around the fort, Hanks probably wished he was back in his native Massachusetts. A veteran of seven years in the artillery, who had inherited the command at Michilimackinac in 1811 upon the death of Captain Lewis Howard, Hanks knew that his post was designed to withstand small-scale Indian attacks, not an assault from the kind of force he could well imagine that the British had landed and certainly not an attack from the north. Even if he held off the first wave, Hanks knew he could not last long because the garrison's source of water was outside the stockade, beyond the protection of the fort's guns.

Around mid-morning the American soldiers could see that the British had occupied the heights behind the fort. Indians could be spotted all over the ridge at the woods' edge, and a six-pounder was directed to the most defenceless part of the garrison." Then the gun boomed out the announcement that Roberts had reached his first objective. Shortly after, a fiag of truce was sent down with Roberts' summons to Hanks to surrender the fort "to His Britannic Majesty's forces." Hanks was urged to surrender "in order to save the effusion of blood, which must of necessity follow the attack of such Troops" as Roberts commanded. He gave the American half an hour to make up his mind. "This, Sir," Hanks later told his superior, "was the first information I had of the declaration of war.

Accompanying the flag of truce were three American civilians who had been taken prisoner by the British and who came down to tell Hanks how useless it would be to fight. The three, Samuel Abbott, Ambrose Davenport, and John Housman—responsible men, all—told the lieutenant that the British were well-equipped and even prepared with ladders and ropes to scale the walls of the fort, should that prove necessary. They exaggerated the size of the British force, but it did not matter since the Americans were outnumbered at least ten to one anyway. Above all, Hanks was advised not to resist because, if even one Indian were killed, a general massacre would result.

Looking up at the barrel of the British six-pounder, glistening in the bright summer sunlight, and the menacing figures of the Indians impatiently awaiting the signal to sweep down on the fort, Hanks made his decision. He informed Roberts that he would surrender.

Around noon, on the "Heights above Michilimackinac," the terms of capitulation were signed. The fort was to be handed over to the British at once. The Americans were to "march out with the Honors of War, lay down their Arms and become Prisoners of War." Under the gentlemanly rules of war of those days, the Americans would be paroled and sent to American-held territory, with Hanks and his officers pledging "their Word and Honor" that none of the men would serve against the British until a regular exchange was arranged. American citizens were given a month in which to take an oath of allegiance to the British or leave for the United States.

Hanks returned to the fort. He and his men marched out, the Stars and Stripes came down, and the Union Jack was run up the flagpole where it waved triumphantly for the first time in sixteen years. The Indians and Canadians went wild. with joy. They ran to their boats, firing off their guns, and, as one American recalled, they "kept up a most hideous yelling, to the consternation of several American prisoners. Then entering their boats and Canoes, at the bow of each were british streamers, made for the harbour facing the fort, and as they approached it, kept up a very animated discharge of small arms." From the fort came the frequent boom of cannon as the British artillerymen answered the salutes of their comrades by firing the captured artillery pieces, a number of which had metal plates attached which stated that the guns had been captured from the British at the battle of Yorktown, some thirty years before.

To Roberts, who was never enthusiastic about employing Indians in combat, it was a matter of immense relief as well as surprise that these warriors had conducted themselves with such restraint. "Not one drop, either of Man's or Animal's blood, was spilt, till I gave an order for a certain number of bullocks to be purchased for them." He praised Askin, Dickson, and the other leaders for the way in which they had handled their charges, but these men were themselves surprised. Askin noted that the Indians had not taken a drop of liquor, "nor even killed a Fowl belonging to any person (a thing never known before) for they generally destroy every thing they meet with."

Thus did the British score the first important victory of the war. One can imagine with what satisfaction Charles Roberts sat down in the officers' quarters at Fort Michilimackinac that night and wrote out his report for General Brock on this bloodless conquest. In a few words he related the measures he had taken and commended "every individual engaged in this Service." Then a disturbing thought crossed his mind, and he concluded by saying, "I trust, Sir, in thus acting I have not exceeded Your Instructions..."

![Homepage [Logo]](/images/logo.png)

![[Public Domain mark]](http://i.creativecommons.org/p/mark/1.0/88x31.png)