War 1812 by George S. May: Chapter 3

III

There can be little doubt what John Askin, Jr., thought of the fort's new commandant. A few weeks after Richard Bullock took over on September 14, 1813, Askin wrote to his son that they had a new captain "who is only St to drive about Miscreants," an ignorant fellow who "pretends to know the difference between Gentlemen & Blackguards." Of late, Askin reported, Bullock was "tormenting all about him with orders counter orders," creating "discontentment & disgust." But this was not all. Madelaine, a Negro slave girl who had "absconded" from Askin a few days earlier, had reportedly been taken into the service of the commanding officer. If this report proved to be true, the aggrieved Indian agent declared, Bullock "must be a damn Scoundrel."

Bullock, however, had more serious problems to concern him than what Askin thought of him. On October 3, an express arrived from General Henry Procter, British commander at Detroit. The news was bad. On September 10, the British navy on the upper Great Lakes had been utterly defeated by the newly-formed American navy under Captain Oliver Hazard Perry, whose terse dispatch, "We have met the enemy and they are ours," wrote an end to British naval supremacy in the Northwest. Subsequently Bullock would learn that Procter, deprived of his naval support, had been forced to pull his troops out of Detroit back into Canada, where, in the first week of October, a slashing attack by an invading American army led by William Henry "Tippecanoe" Harrison completely routed Procter's army.

To complete the defeat of British forces in the upper Great Lakes, Harrison planned to send an expedition north that fall to capture Michilimackinac. However, the departure of the expedition was delayed until it was so late in the season that Harrison and the naval officers decided that it would be too risky to chance a foray so far north as the Straits of Mackinac, and the plans were shelved until the following summer.

It really did not seem to matter since it appeared likely that the British on Michilimackinac, with their lifeline from the supply bases on Lake Erie cut, would soon wither on the vine. By mid-October, when the North West Company's 100-ton vessel, the Nancy, returned to Michilimackinac with a report that it had barely escaped capture when it was attacked by Americans on the St. Clair River, Captain Bullock knew how perilous his position was. Only the waters of Lake Huron separated him from the triumphant Americans. Foremost in his mind, however, was not the possibility that an American naval force might at any moment land troops on the island, but the very real possibility that he and his men might starve before spring. William Bailey, in charge of the fort's commissary, gravely reported that there was scarcely a month's supply of food left. The situation was truly desperate. "I really & sincerely believe," John Askin, Jr., told his son, "that we will be obliged to eat every horse that is on the Island before spring if we are not taken prisoners this autumn."

The only hope of replenishing the fort's cupboards seemed to lie in bringing provisions from Lake Ontario to the mouth of one of the rivers emptying into the southern part of Georgian Bay and then transporting them by water to the island. Late in October, Robert Dickson arrived from the east with word that the British were sending pork and Hour to Matchadash where boats from Michilimackinac could pick them up. Disregarding the warnings of old-timers, who told him that it was too late in the year for such a venture, Bullock sent two large canoes and a bateau to Matchadash, hoping they could get back with supplies before winter closed off any further travel on the lakes. In a few days the bateau and one of the canoes returned, the Indians who manned them insisting on turning back when ice started to crust the water's surface. The other canoe managed to get through to Matchadash, only to find that the promised supplies had not been sent up.

Fortunately for the British on Michilimackinac, William Bailey purchased, "at most exorbitant prices," enough food from the islanders and from the few small settlements nearby so that the garrison would be able to survive, by strict rationing, until navigation opened in the spring and provisions could be brought in. It was a tight squeeze, however. On Christmas Day the soldiers learned that meat would be issued to them only four times a week. In March the meat gave out completely, and the garrison lived on corn and fish the remaining weeks of the long Mackinac winter.

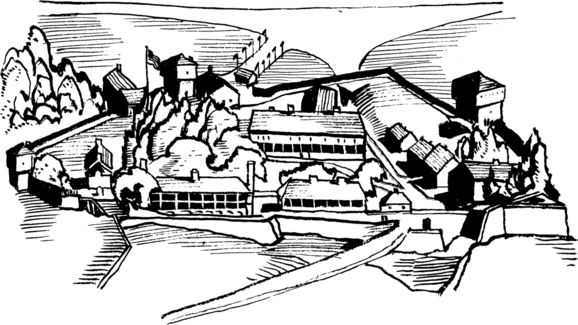

Although spring would bring them relief, Bullock and his men almost dreaded the time when the ice broke up because that would herald the opening of the invasion season for the Americans. Bullock and Robert Dickson had conferred in October, 1813, about measures that should be taken to defend the island against the anticipated attack. To protect the new supply line from Georgian Bay, gun boats would have to be built there during the winter. On the island a blockhouse would have to be constructed on the high ground north of the fort to guard against a repetition by the Americans of the successful tactics used by Captain Roberts in 1812. The old well inside the fort should be reopened so that, in the event of a siege, the garrison would not be dependent on the outside water supply. If all this were done and if about two hundred more infantrymen and artillerymen and two sixpounders were brought in and three hundred Indians were available, Bullock and Dickson believed they could hold the island.

In general these recommendations were carried out. The British were determined to retain control of Michilimackinac, knowing that if they lost it they would lose control over the Indians in the northern Great Lakes and with it much of their control of the fur trade. From Downing Street in London came orders to build a naval force on Lake Huron to defend the supply route to the Straits of Mackinac. In Montreal the dire need for reinforcements for Fort Michilimackinac was pointed out in a memo that circulated in government circles and which laid bare the weakness of the existing garrison. "The veterans are drunken old men, and helpless, & the Michigan Fencibles... only fit for being boat men & little to be depended upon."

As a result of furious activity in many quarters, the British position in northern Lake Huron was vastly improved by the summer of 1814. During the winter Captain Bullock strengthened the pickets and otherwise tidied up the defenses of Fort Michilimackinac. In the spring, construction of the new fortification on the high ground back of the fort was rushed forward. In later years old residents recalled that each villager had to donate a certain number of days of labor on this project. The new fort was completed in July and was dubbed Fort George after the reigning British monarch, George III, although it is doubtful that the king, now hopelessly insane, was aware of the honor that his subjects in this far-off corner of the empire had bestowed on him. With the completion of this fortification the back door to Fort Michilimackinac was effectively guarded from attack.

Meanwhile, the British in Canada were taking steps to see that supplies and reinforcements got through to Bullock as soon as possible in the spring. Several batteaux were built at Nottawasaga Bay. A small cannon could be mounted in the bow of these boats which would furnish a little protection against a small enemy raiding party. A hundred members of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment were brought up to await transportation to Fort Michilimackinac. Large quantities of flour, biscuits, pork, salt, and rum were collected at the embarkation point also. In charge of the operation was a Scotsman, Lieutenant-Colonel Robert McDouall, a veteran of eighteen years service in the British army and recently aidede-camp to General Procter. Late in April the troops and the supplies were loaded in the boats, and the voyage of about 250 miles to Mackinac Island began.

The arrival in the spring of the first vessel from down below has always been a dramatic event in the lives of the inhabitants of the island, but never was the drama and the excitement greater than on that May day in 1814 when soldiers and civilians hurried down to the shore to welcome McDouall and his men and to lend an eager hand in unloading the long-awaited barrels and bags of provisions. There had been many who had wondered if the first arrivals at the Straits that spring would be flying the Stars and Stripes and firing cannon as they came.

About the same time as the British reinforcements landed, the Indian warriors began to arrive and in such numbers that McDouall, who assumed command of Fort Michilimackinac on May 18, soon was appealing to General Gordon Drummond, new commander in Upper Canada, to send more supplies since the food that had just been brought in would rapidly be consumed. When Robert Dickson arrived once more with several hundred Indians from the west, McDouall reported that his daily issues of food numbered about 1,600.

The fifth of June was the king's birthday and to celebrate the occasion McDouall spoke to the assembled Indian chiefs and warriors. He thanked them for demonstrating anew their loyalty to the British by hurrying to defend Michilimackinac in this critical hour. He sought to set at rest the fears that American agents in recent months had been spreading that those Indians who did not make their peace with the Americans now would be sternly punished in the future. Do not be deceived by the "artifice & cunning" of the Americans, the British officer warned. Were any of his listeners, he asked the Indians, "so blind & infatuated" that they could not see that the Americans would be satisfied only when the Indians had been destroyed "root and branch" and all the Indians' lands had been seized' "My children," he cried, "You possess the Warlike spirit of your Fathers. You can only avoid this horrible fate by joining hand in hand with my warriors in first driving the Big Knives from this Island, & again opening the great road to your Country."

McDouall's concluding exhortation rose to Shakespearean-like heights of eloquence. "Happy are those warriors who rush into the fight, having justice upon their side," the colonel intoned in his Scottish brogue. "You go forth to combat for the tombs of your forefathers, and for those lands which ought now to afford shelter and sustenance to your wives and children. May the Great Spirit give you strength and courage in so good a cause, and crown you with victory in the day of Battle."

Unfortunately the Americans did not cooperate by putting in an appearance, and as the days stretched into weeks and still no sign of the enemy, the Indians became restive and impatient. There was talk of setting out down Lake Huron to meet the Americans on the way up a scatterbrain proposal since nothing the British and the Indians could put in the water could offer any effective resistance to the kind of naval power the Americans now had at their disposal. So the British waited on the island with one half of the garrison being assigned each night to posts on the ramparts of the fort to guard against a sudden surprise attack

Toward the end of June two men beached their canoe and hurried into the village with information that threatened to upset the British strategy. A detachment of American soldiers under General William Clark (of Lewis and Clark fame) in May had occupied the Mississippi River trading post of Prairie du Chien and had started building a fort. Most of the Indians and Canadians who were there had fled at the Americans' approach, but several Winnebago Indians had been killed while trying to escape capture.

News that American troops were in the heart of an area dominated by the British for a half century caused great alarm on Michilimackinac. The Winnebago and Sioux warriors who had come to defend the island now wished to return home to defend their families from the Americans. British fur traders were much perturbed, too. "We must go and take the fort!" the veteran trader, Thomas Anderson, cried, and he quickly organized an impromptu company of sixty traders and voyageurs who were willing to follow him. Anderson then went to Colonel McDouall, seeking official backing for the raid. Even though it meant weakening his forces on Michilimackinac at a time when he needed every man he could get, McDouall felt that he had to do everything he could to drive the Americans from Prairie du Chien. As he later explained: "it must either be done or there was an end to our connection with the Indians... & thus would be destroyed the only barrier which protects the Great trading establishments of the North West & the Hudson's Bay Company."

So the expedition was organized, composed of Sioux and Winnebago Indians, volunteers enlisted by Anderson and other traders, several "smart fellows" of the Michigan Fencibles, and, most important of all, Sergeant James Keating of the Royal Artillery and a little three-pound cannon which McDouall agreed to part with chiefly because it would bolster the morale of the Indians. William McKay, an old trader who had been captain of the Michigan Fencibles but "whose entire knowledge of war matters," according to Thomas Anderson, "consisted of his predilection for rum," was placed in charge of the operation with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

On June 28, the fleet of batteaux and canoes started on the long trip to Prairie du Chien with a noisy send-off from the cannons of the fort. About a month later the British learned that McKay and his motley force had scored a resounding victory. Due to the skillful use of the three-pounder by Sergeant Keating, the American garrison at Prairie du Chien was compelled to surrender on July 20, ending the threat to continued British control of the Upper Mississippi. This heartening news came at a time when the British needed. cheering, for at the end of July the Americans finally arrived off Michilimackinac.

The American army-navy operation against Fort Michilimackinac had been bungled virtually at every step. In April, Captain Arthur Sinclair had been put in command of the naval squadron. Ships made famous in Perry's victory were included—Perry's flagship, the Lawrence, the Niagara, from whose decks Perry fought on when his flagship was disabled, the Scorpion, and the Tigress. The Caledonia, which had been captured by the Americans late in 1812, was also part of the feet, thus earning the unique distinction of participating in both the British and American expeditions against Mackinac Island.

Disputes within the American high command, however, delayed the departure of the feet. One of these had to do with the command of the troops, originally slated to have been given to Major Andrew Hunter Holmes, a Virginian who had distinguished himself in a raid into Ontario in February. Harrison objected to this assignment. Eventually, Lieutenant Colonel George Croghan, a twenty-two-year-old Kentuckian and hero of the defense of Fort Stephenson, Ohio, in 1813, was given the command of the more than seven hundred soldiers, with Holmes as second in command.

The expedition left Detroit on July 3, proceeded with difficulty through the St. Clair Flats and finally sailed into Lake Huron on July 12. Sinclair and Croghan had orders to destroy the installations supposedly built by the British on Matchadash Bay, but, incredibly, no one knew how to get to Matchadash After wasting several days, Croghan and Sinclair gave up and proceeded north not to Michilimackinac, but to St. Joseph's where they burned the fort, now abandoned by the British. A force led by naval Lieutenant Daniel Turner and Major Holmes went up the St. Mary's River, burning one of the North West Company's ships and seizing or destroying the Indian trade goods at John Johnston's Sault Ste. Marie post. Johnston himself was absent, having led a company of Canadian volunteers to Michilimackinac to help out the British.

At long last, around daybreak on July 26, British sentinels sighted the American feet moving toward Michilimackinac from the east By sunset the village was deserted, the residents gladly obeying McDouall's orders to move up to the fort where they would be protected from the American guns and the expected attack. Anxiously everyone on the island waited and waited but still the Americans did not make their move. Did American leaders, McDouall wondered, realizing how low the British food supply was, plan to blockade the island and starve the British into surrendering'

Actually, although the capture of Michilimackinac was the whole purpose of the American expedition, little serious thought seems to have been given to how to achieve this objective. Despite the fact that Ambrose Davenport and other former residents of the island accompanied the expedition, while the army had many men who had served at the fort, Sinclair and Croghan acted as if they had not been thoroughly briefed on the problems they would encounter. As a result, they fumbled about trying to decide how to attack the British.

The feet first anchored off the eastern end of Round Island but soon withdrew toward Bois Blanc Island when the fire from the British guns came too close for comfort. Next a small party was sent to reconnoitre Bound Island with a view to setting up a gun position there which could help to cover a landing on the southern end of Mackinac Island. The Americans were soon spotted. Indians on Michilimackinac jumped in their canoes and raced across toward Round Island. The Americans hastily got back into their boats and departed, exchanging a few harmless shots with the approaching Indians. One of the Americans reportedly did not reach his boat in time and was captured. When the Indians returned to Michilimackinac, a strong guard of British redcoats rescued the captive from the excited natives who were having their first chance to release some of their pent up war emotions.

Next day during a brief exchange of shots between the Lawrence and the British guns on shore, Sinclair made the embarrassing discovery that the American ship's guns could not be elevated enough to enable them to hit Fort Michilimackinac. With eighteen thirty-two pound carronades and two long twelves each, the Lawrence and the Niagara could have wrought immense destruction could their guns have been trained on the fort. Any thought of making a frontal attack on the fort was now dismissed from the American leaders' minds since to have attempted such an attack without the covering fire of the fleet would have been suicidal.

Bad weather hampered any further action by the Americans for several days. During this period, Croghan reported to the secretary of war, he decided to land at some favorable point on the island, fortify the position, and, through the use of his artillery, which he believed superior to that of the British, "to annoy the enemy by gradual and slow approaches." It was argued that if he succeeded in establishing himself on the island, the British would have to attack him or risk the loss of their Indian and Canadian allies, "as they would be very unwilling to remain in my neighbourhood after a permanent footing had been taken."

In his report to the secretary of the navy, Arthur Sinclair painted an entirely different picture of this operation. He strongly implied that young George Croghan had lost whatever enthusiasm he had ever had for the Michilimackinac campaign. The military commander, Sinclair said, was convinced "that the Indian force alone on the island, with the advantages they had, were superior to him." He went through the motions of making a landing only as a means of proving to the government that he could not drive the British off the island with the forces at his disposal.

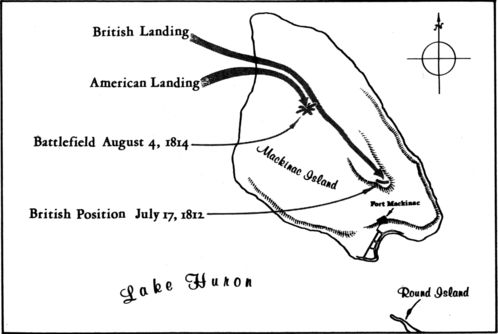

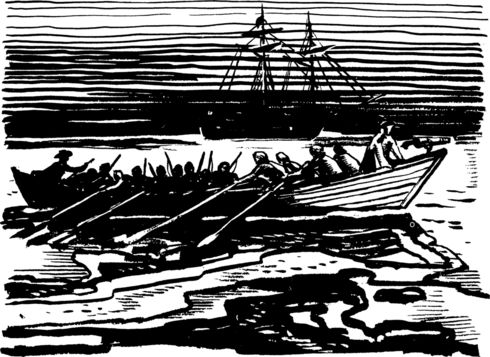

On the morning of August 4, nine days after the American arrival, the weather cleared. Sinclair anchored three hundred yards off British Landing on the west side of the island. After what a British officer described as "a tremendous fire, which completely swept the landing place," American troops were sent in, hitting the beach where Captain Roberts and his men landed two years before. The immediate objective was an open field some distance inland where former residents told Croghan he could dig in Leaving two companies of marines and regular army men as a reserve force, Croghan pushed forward with the rest of his men through a wooded area to the edge of the open ground, at which point he learned that the British were in front of him at the opposite end of the field.

When he knew where the Americans planned to attack, Colonel McDouall left only twenty-five Canadian militia in each of the two forts and took the remainder of his command some 140 soldiers and volunteers, an artillery battery, and about 350 Indians out to meet the invaders. The British troops were drawn up on commanding ground, behind natural breastworks, athwart the route to the south. In front of them was a clear field of fire. To their rear and on their flanks were thick woods in which the Indians were posted Mc.Douala's total force was probably about equal numerically to that which Croghan had with him, but McDouall was worried about the reliability of his Indian allies.

When the Americans appeared at the edge of the woods across the field, the Royal Artillery opened fire, doing no damage but creating some confusion in the American ranks. Croghan brought up his artillery and returned the British fire, but his artillerists, too, for the most part were well off their intended targets. After a time the guns became silent, and the Americans were observed regrouping their forces.

At this time McDouall received a report, which turned out to be false, that troops from the Lawrence and the Niagara had landed farther south, to the rear of the British position, and were moving across the island to attack the virtually defenceless forts. McDouall pulled back part of his force to meet this threat, and most of the Indians rushed back, expecting to ambush the Americans.

A small band of Menominee Indians under Chief Tomah stayed in their position on the left flank of the British. They were hidden behind rocks and boulders and trees which they had felled to form breastworks. Among this group was L Espagnol, a six-foot-two warrior, "rawboned and powerful," who claimed to be part Spanish. His nephew, Yellow Dog, was beside him, and when the other Indians were seen moving back south, Yellow Dog said, "Uncle, let us go with the others." L'Espagnol replied, "No, I shall remain; if you wish to go, you can; but you ought to show proper respect for your uncle by standing by him."

Just then an American force was seen approaching. Regular army troops under Major Holmes had been sent off on a quick movement to the Americans' right, in an effort to turn the British flank. The officers and a small bodyguard were out in front. Yellow Dog picked out one officer, gaudily dressed, the sun reflecting off his silver braid. L'Espagnol rewarded his nephew for sticking with him by letting Yellow Dog have the honor of shooting this fancy officer, while he contented himself with a more conservatively-dressed officer who was casually swinging his sword, unaware that death was near. At a signal, the Indians let loose with their war cry and simultaneously opened fire. Yellow Dog's gun misfired, but his uncle's did not, and Major Holmes fell dead, his sword and cap lying forward. L'Espagnol leaped forward, seized these trophies and then fell back into the dense forest, his nephew following him.

Tomah's men completely stopped the attempted flanking movement, killing Holmes, severely wounding the second in command, Captain Desha, and inflicting other casualties. Leaderless, the Americans fell back in confusion, while McDouall, hearing the Indian war cry, returned with the men he had taken south. Croghan sent more regulars directly against the main British position, forcing McDouall to withdraw. But the Americans found themselves under fire from the Indians on either side of them while the British had merely taken a position on higher ground. Recognizing the hopelessness of the situation, Croghan ordered a retreat back to the shore. Had the order not been given, an American officer who visited the battlefield after the war declared, Croghan's army "would inevitably have been destroyed."

The demoralized Americans returned to their ships and counted up their losses. Holmes and twelve privates had been killed. Three officers and forty-eight men had been wounded, and two men were missing. Within a week, two of the officers and five of the men would die of their wounds. British and Indian losses are not known but were certainly much less than those of the Americans.

The American ships returned to their Bois Blanc anchorage. On the morning of August 5, permission was granted by McDouall to an American detail to recover the body of Major Holmes, which, with the bodies of other Americans, had been left on the field. Holmes' Negro servant had hidden his master's body under some leaves, and it was found by the Americans, untouched by the Indians. A wounded American who had been captured by the British was returned to the Americans. This man and another. wounded American had been taken to Fort Michilimackinac after the battle. According to Henry B. Schoolcraft, John Johnston's daughter, Jane, Schoolcraft's future wife, and Rosette Laframboise, who would later marry Franklin Pierce's brother, made new linen garments for the two men, who had been virtually stripped of their clothing. One of the men died of his wounds that night.

But there is another, and a ghastly account of the treatment accorded the American dead and wounded. Several persons who claimed to have witnessed this treatment or had arrived on the island shortly afterward declared that American dead had been barbarously mutilated. Indians were seen to return to the fort "some with a hand, some with a head, and some with a foot or limb." Parts of the bodies were said to have been placed on poles for ten days in the Indian burial ground. John Jacob Astor's nephew, George Astor, and "two respectable ladies" later told Arthur Sinclair that the wounded American did not die, he was murdered. The Indians, they swore, cooked and ate the hearts and livers of the American dead, "and that, too, in the quarters of the British officers, sanctioned by colonel M'Dowall." It is apparently impossible to determine the truth of these charges, although these were by no means the only reports of such atrocities having been committed during the war.

The Americans had had their fill of Michilimackinac, but they could still bring the British to their knees by cutting the remaining supply lines to the island. Therefore, while the Lawrence and the Caledonia were sent to Detroit with the sick and the wounded and part of the troops, Sinclair and Croghan took the rest of the expedition to Nottawasaga Bay from which point, they had learned, McDougall was supplied. Two miles up the Nottawasaga River on August 14 the Americans destroyed a blockhouse and the schooner Nancy, loaded with shoes, leather, candles, flour, pork, and salt for Michilimackinac. Having destroyed the last vessel of any size that could be used to supply the British garrison, Croghan and Sinclair returned to Detroit in the Niagara, while the Scorpion and the Tigress were left to see that the supply lines to Michilimackinac stayed closed until winter set in.

Lieutenant Miller Worsley of the Royal Navy, who was in charge of the Nottawasaga base, escaped with seventeen men and made his way in a canoe to Michilimackinac, arriving on August 31. He found the British garrison was on half rations. The few horses on the island had been killed and salted down in a desperation measure, but starvation was a certainty unless supplies arrived. But how could they be brought past the American ships) Worsley had a plan. On the way up he had sighted the Scorpion and the Tigress, anchored about five leagues apart near St. Joseph's. These vessels were really only large gunboats, the Scorpion having two guns, the Tigress only one. Worsley told McDouall that the British could surprise the Americans, capture their boats, and break the blockade.

The following day, therefore, four batteaux were fitted out, a small gun being mounted in the bow of two of them. Worsley and his men manned one of the boats, while fifty members of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, many of whom had been fishermen and were accomplished sailors, took the other three boats. The little flotilla set out that evening, accompanied by several canoes of Indians, led by Robert Dickson.

The following evening the party reached the Detour, south of St Joseph's, where they remained in hiding until six o'clock the next night, September 3, when Worsley and his four batteaux rowed silently for six miles toward where the Tigress was anchored. Three hours later they sighted the boat through the darkness and were within a hundred yards of her before the Americans saw them and called upon them to identify themselves. The British made no reply, and the Americans opened fire with their 24-pounder and their muskets. Within five minutes, however, the British had reached the American vessel, boarded her, and overpowered its crew of thirty men, after a short, bitter fight. The British lost two men killed and seven wounded, while three Americans were killed, and several wounded, including Sailing Master Champlain and the other officers.

On the following day the Americans were sent under guard to Mackinac Island. On September 5, the Scorpion was seen approaching in the distance. The British had not altered the position of the Tigress, which was still Hying the American flag. The British soldiers stayed below or laid down on the decks so as not to be seen. The ruse worked. The Scorpion anchored two miles away that night, its commander, Lieutenant Daniel Turner, having no reason to suspect the presence of the enemy aboard his sister ship. Early next morning Worsley pulled up anchor and set out toward the American ship. Using signals from the American signal book which was found on the Tigress, Worsley was within ten yards of the Scorpion before Turner discovered what was happening. It was too late then. The British quickly boarded the Scorpion and seized control of it with little resistance being offered.

Worsley and his men sailed triumphantly back to Michilimackinac where the populace greeted them with wild enthusiasm—as well they might. British naval supremacy, at least in northern Lake Huron, had been restored, and as a result the remaining weeks of navigation that fall saw a steady procession of batteaux coming from Georgian Bay to Mackinac Island with presents for the Indians and enough food to take the islanders safely through another winter.

The capture of the Scorpion and the Tigress, which Arthur Sinclair rightly described as mortifying" to the Americans, ended the war on the northern Great Lakes. Through a combination of their own great resourcefulness and the ineptness of their opponents, the British had. held Michilimackinac throughout the war and from it had been able to keep control over a vast area north of Detroit. Fortunately for the Americans, the Treaty of Ghent, signed December 24, 1814, provided that both sides were to relinquish all territory which had been conquered during the war.

"Our negotiators, as usual, have been egregiously duped, Colonel McDouall commented bitterly the following spring when he learned of the terms of the treaty. "I am penetrated with grief at the restoration of this fine Island—a Fortress built by nature for herself." He had his orders, however, and they left him no choice. He delayed the surrender of the post until he had made some provision for housing his men at a new fort to be built on Drummond Island and until British traders had had a chance to pass through to the west without having to pay the duties that would be levied when the Americans took over.

Finally, on July 18, 1815, three years and a day after Lieutenant Porter Hanks and his men marched out of Fort Michilimackinac, Colonel Anthony Butler and troops of the Second U. S. Regiment of Riflemen arrived, and McDouall turned the island over to him. The Stars and Stripes once again waved in the summer breeze over the fort.

![Homepage [Logo]](/images/logo.png)

![[Public Domain mark]](http://i.creativecommons.org/p/mark/1.0/88x31.png)