War of 1812 History: 1813

In 1813, there was action along a large number of fronts. In a linear narrative like this one, it can be hard to keep everything straight, but we'll try. The following story of 1813 will work roughly from West to East, with occasional jumping from one venue to another where it makes sense.

In the Lake Erie region, the Americans' first goal was the recapture of Detroit; they had sent Major-General William Henry Harrison, who had been in the north-west for a while and who would later become president of the United States for about a month, to look after that. Harry Procter, whom Brock had left in charge at Detroit last year, was victorious over an advance guard under Brigadier-General James Winchester, whom he met at Frenchtown. Harrison retreated to Fort Meigs, and Procter marched to the fort but couldn't capture it.

In the Lake Erie region, the Americans' first goal was the recapture of Detroit; they had sent Major-General William Henry Harrison, who had been in the north-west for a while and who would later become president of the United States for about a month, to look after that. Harry Procter, whom Brock had left in charge at Detroit last year, was victorious over an advance guard under Brigadier-General James Winchester, whom he met at Frenchtown. Harrison retreated to Fort Meigs, and Procter marched to the fort but couldn't capture it.

Meanwhile, both sides had been building a fleet on Lake Erie. The British had the lead in the ship-building contest, which allowed them to blockade the American harbour at Presqu'ile so that the American fleet couldn't get out. However, Robert Barclay, who was in command of the British fleet, had a problem. He was low on supplies, so on July 29th he raised the blockade to pick up a shipment of supplies at Long Point. The shipment wasn't there. Now Barclay had two problems: He was low on supplies, and there was an American fleet, under the command of Oliver Hazard Perry, on the lake. Due to the miracle of shoddy construction, the American fleet significantly outnumbered the British fleet. Barclay retreated to Amherstburg. On September 10th, desperately low on supplies, he was forced to confront Perry near Put-in-Bay, Ohio. Perry's flagship, named the Lawrence after the late James Lawrence (see below), was severely disabled early in the encounter; Perry, living up to his middle name, had his men row him, under heavy gunfire, from the Lawrence to the still-fresh Niagara, a distance of about ½-mile, and he transferred his command to the latter ship. Don't try this at home, but it worked for Perry. The Americans won a decisive victory, capturing all six British vessels.

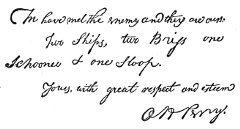

Perry's report of the battle to Harrison contains the famous line "We have met the enemy and they are ours." The American victory gave them control of Lake Erie, which they managed to retain for the rest of the war. Procter's supply lines were cut, and he had to retreat from Detroit. Tecumseh referred to Procter as

a "fat dog that carries its tail on its back, but when

affrighted drops it between its legs and runs off."

with regard to this action, but accompanied him into Upper Canada.

Procter retreated very slowly through Upper Canada,

allowing Harrison to catch up with him near Moraviantown. The British didn't really bother putting much effort into fighting, preferring to retreat while their Indian allies fought bravely against long odds. Tecumseh himself was killed on the field of battle and the Indians were soundly defeated. There are about two dozen stories about what happened to Tecumseh's body; most likely, someone buried him somewhere unknown. Procter didn't win any awards for bravery for this battle. Rather, his cowardice earned him a court-martial, as a result of which he was removed from command and received a six-month suspension.

Perry's report of the battle to Harrison contains the famous line "We have met the enemy and they are ours." The American victory gave them control of Lake Erie, which they managed to retain for the rest of the war. Procter's supply lines were cut, and he had to retreat from Detroit. Tecumseh referred to Procter as

a "fat dog that carries its tail on its back, but when

affrighted drops it between its legs and runs off."

with regard to this action, but accompanied him into Upper Canada.

Procter retreated very slowly through Upper Canada,

allowing Harrison to catch up with him near Moraviantown. The British didn't really bother putting much effort into fighting, preferring to retreat while their Indian allies fought bravely against long odds. Tecumseh himself was killed on the field of battle and the Indians were soundly defeated. There are about two dozen stories about what happened to Tecumseh's body; most likely, someone buried him somewhere unknown. Procter didn't win any awards for bravery for this battle. Rather, his cowardice earned him a court-martial, as a result of which he was removed from command and received a six-month suspension.

On the Niagara Frontier, the Americans under General Henry Dearborn significantly outnumbered the British again this year. Despite superior numbers, however, their efforts were, to put it nicely, a little less than entirely successful. First, aiming to destroy the war-ships resting at York for the winter, they landed at York on April 27th, only to find that one off the two ships has already left. While they were there, the magazine exploded, tossing 250 American soldiers into the air. The Americans did capture the Royal Standard (the flag of the King), a unique event in the history of the British Empire. The Americans then sacked York, including burning the Parliament buildings. After a few days the Americans left, later capturing Fort George. Meanwhile the British decided to strike at Sackett's Harbour, opposite Kingston. The battle got off to a rough start for the British, so Prevost called off the assault, even though it had started to appear that things would work out (this was a bit of a bad habit of Prevost's).

Following the capture of Fort George, the Americans swept down towards Burlington Heights. They were stopped at Stoney Creek in a fierce night attack (before daybreak in the wee hours of June 6) during which the two American generals were taken prisoner.

![Laura Secord [Laura Secord]](/images/laura_secord_psh_203a_small.jpg) A few weeks later around 500 Americans, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Bœrstler tried to surprise the British at Beaver Dams, near Thorold. In charge there for the British was Lieutenant James Fitzgibbon, a talented officer who was yet of low rank, partly due to lack of money to purchase promotions. Fitzgibbon had previously served in Holland, as one of the ten thousand or so men under the Grand Old Duke of York, and all that marching up to the top of the hill and down again did nothing for his career. Brock, however, noticed Fitzgibbon's potential and promoted him out of the ranks. Fitzgibbon was, as Bœrstler was about to find out to his dismay, not at all surprised about the impending attack, because he knew all about it, thanks to a brave woman by the name of Laura Secord and the Indians, and it was the Americans that were surprised in an ambush attack and defeated by a much smaller force. After this, the Americans didn't venture out beyond Fort George too much. After this mediocre performance, Dearborn was recalled for what were politely described as "health reasons" on July 6th. The Niagara frontier remained quiet for the next five months, with the British troops outside Fort George blockading the Americans for most of the summer, and the Americans having their sights further to the east in the autumn.

A few weeks later around 500 Americans, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Bœrstler tried to surprise the British at Beaver Dams, near Thorold. In charge there for the British was Lieutenant James Fitzgibbon, a talented officer who was yet of low rank, partly due to lack of money to purchase promotions. Fitzgibbon had previously served in Holland, as one of the ten thousand or so men under the Grand Old Duke of York, and all that marching up to the top of the hill and down again did nothing for his career. Brock, however, noticed Fitzgibbon's potential and promoted him out of the ranks. Fitzgibbon was, as Bœrstler was about to find out to his dismay, not at all surprised about the impending attack, because he knew all about it, thanks to a brave woman by the name of Laura Secord and the Indians, and it was the Americans that were surprised in an ambush attack and defeated by a much smaller force. After this, the Americans didn't venture out beyond Fort George too much. After this mediocre performance, Dearborn was recalled for what were politely described as "health reasons" on July 6th. The Niagara frontier remained quiet for the next five months, with the British troops outside Fort George blockading the Americans for most of the summer, and the Americans having their sights further to the east in the autumn.

In October, John Armstrong, the U.S. Secretary of War, had written Brigadier-General George McClure, in command at Fort George, advising him that, if necessary to defend Fort George, he might need to destroy the neighbouring town of Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake). McClure interpreted this letter to mean "evacuate Fort George and burn Newark to the ground", which he did on December 10th, leaving some of the residents to perish in the snow. By this time, the British had a new general in command of the forces in Upper Canada, Gordon Drummond. After Brock's death in 1812, there had been a problem finding a talented person to fill the top position in Upper Canada. Drummond wasn't quite Brock's equal either, but he was energetic, resourceful, and well-liked. As a bonus, he was Canadian-born. Colonel Murray re-took Fort George on the 12th, and made plans to take Fort Niagara, the American fort opposite, which Drummond approved. Fort Niagara fell on the 18th. The British progressed south along the Niagara River, burning all of the American forts and settlements there, as far as Buffalo.

Moving eastward, control of Lake Ontario went back and forth during the year. By the fall, the Americans, under Commodore Isaac Chauncey, had, by virtue of quick, shoddy construction, obtained the upper hand on Lake Ontario. However, Chauncey was unable to obtain a decisive victory over the British fleet under Sir James Yeo. American control of the lake did, however, make it possible for the Americans to transport 4,000 troops under Major-General James Wilkinson in October from Niagara to the other side of the lake for a movement against Montreal.

Wilkinson, who was now in charge of the American troops in this sector after Dearborn's "reassignment", was a Kentuckian with Revolutionary War experience and an out-and-out scoundrel. A two-pronged attack was arranged on Montreal, with one army under Wilkinson landing below Prescott and marching north-east and another army under General Hampton marching along the line of the Richelieu. Since Wilkinson and Hampton had no interest in communicating with each other, it's probably no surprise that this attack didn't work out. Hampton was defeated at Châteauguay on October 26th. Wilkinson was defeated at the Battle of Crysler's Farm on November 11th, and retreated shortly afterwards. In both battles, the British were significantly outnumbered.

On the Atlantic Ocean, for the most part, the Americans were winning most of the individual battles. However, on June 1st, 1813, the British frigate Shannon captured the American frigate Chesapeake and sailed the vessel to Halifax. Mortally wounded, just before being carried below the deck, Captain James Lawrence of the Chesapeake gave his last command, "Don't give up the ship", thus coining a new phrase. His officers then promptly gave up the ship. Captain Broke of the Shannon had been severely wounded during the fight, so the command of the vessels devolved upon 22-year-old Second Lieutenant Provo Wallis, who would eventually become Admiral of the Fleet, not so much because of his skill demonstrated in the capture of the Chesapeake, but because the British Navy would eliminate mandatory retirement for Napoleonic War veterans and base promotion on seniority, and Wallis lived to the age of 100. The British promoted this capture all out of proportion to its actual significance. What was more significant was that, starting in the spring, the British were now blockading all of the American coast, with the exception of New England.

Meanwhile, the American southwest became a theatre of operations. Before going north, Wilkinson had captured part of West Florida which was claimed by both Spain and the United States. In the late summer, the Creek Indians in Georgia and the Southwest Territory rose up, and massacred hundreds of settlers, militia, and other Creeks. Andrew Jackson organized the local militias. He would eventually decisively defeat them at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend on March 27th of the next year, and the Creeks were forced to cede a large amount of territory to the United States.

![[Creative Commons Licence]](http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by-sa/2.0/ca/88x31.png) Copyright/Licence: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Canada License. See also copyright information for this page.

Copyright/Licence: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Canada License. See also copyright information for this page.

![Homepage [Logo]](/images/logo.png)