Canada and Canadian Defence: Chapter 6

Chapter VI

Changes affecting defence since 1814, and their influence—The Canadian boundary-line—The Rush-Bagot Convention—The situation on the lakes—The general introduction of steam and electricity—Canals—Railways—Increased importance of cities, towns, etc.—Change in modern weapons and warfare—Methods, but not necessity, of defence altered.

Among the changes affecting the defiance of the Canadian frontier which have taken place since the war of 1812–14, it is convenient to mention first some alterations made in the boundary-line of Canada.

This is now, on the south, as far west as the Mississippi, much what it was in 1812–14, and much as it had been defined (as far as was then practicable) in 1783, after the declaration of American Independence; but there have been modifications.

In 1783 the country traversed by this line was unsurveyed, and in parts entirely unexplored.1 The course of certain rivers and watersheds laid down as forming the boundary, and even the identity of the St. Croix, one of these rivers, became afterwards matters of controversy, leading to various arbitrations, treaties,2 commissions, and conventions, most of which have taken place since the peace (under the Treaty of Ghent) of 1814. On the north-west, also, in 1867, the United States purchased the territory of Alaska from Russia, out of which grew the Alaska Boundary Commission of 1898.

Occasionally the disputes leading to, and the decisions of these arbitrations, etc., have produced irritation and bitter feeling between the United States and Canada. It is needless to dwell on this here, but necessary to allude to the Ashburton Treaty of 18421—one which, rightly or wrongly, caused much heartburning in the Dominion.

Under this, some seven-twelfths of the territory between Maine and New Brunswick, to which Canada laid claim, was awarded to the United States, and only five to her, the result being that the communication between Quebec and Halifax was made more circuitous—non-British territory being interposed within a few miles of the most direct route.

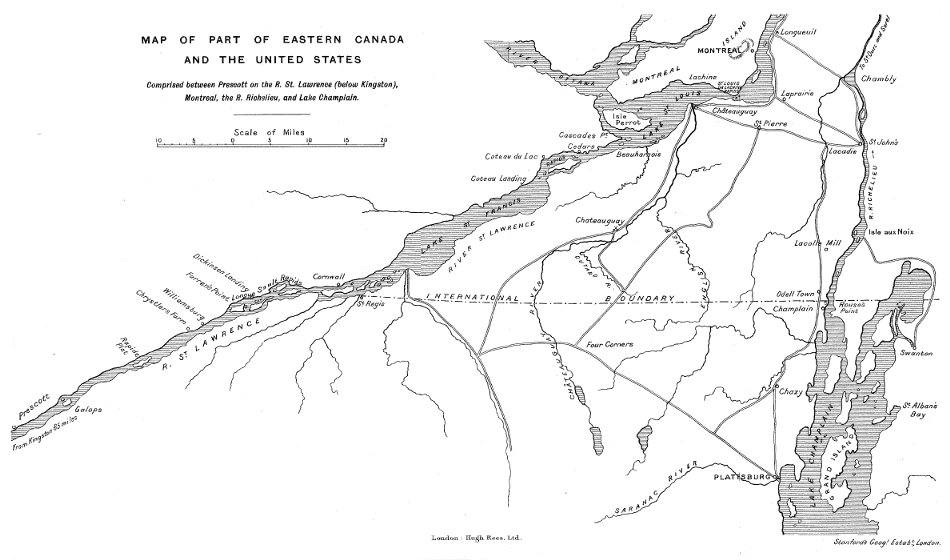

Rouse's Point, also, commanding the junction of Lake Champlain with the River Richelieu, became an American post.2

In that part of the boundary-line between Lake Superior and the Pacific Ocean there have been, too, under various treaties, certain alterations; but the principal point to draw attention to here is that in 1812–14 the district west of Lake Superior was too little known, as well as too difficult of access, too rugged and thinly populated, to become the theatre of war on any scale in an invasion of Canada. Necessarily, as years go on this immunity from attack of so important a region will grow less and less. Indeed, the time has already arrived when the defence of this part of the frontier, west of Lake Superior, including the cities which are near it, must be seriously considered. Such defence demands free access on the ocean to the Canadian Pacific ports, and therefore naval power on Pacific waters.

In the same way, the defence of the frontier between Canada and Alaska, and of that towards Hudson Straits, which in 1812–14 did not in any way call for attention, must in the future do so.

Before passing on to other matters, it may be useful to mention that a complete summary of all the alterations which have been made in the International boundary between Canada and the United States is given in A History of Canada, 1763 to 1812, by Sir C. P. Lucas, appendix, pp. 321–351 (1909). The various treaties, etc., are also referred to in Documents Illustrative of the Canadian Constitution, by William Houston, M.A., Librarian to the Ontario Legislature (1891); and in British and American Diplomacy affecting Canada, 1782 to 1899, by Thomas Hodgins, Q.C. (Toronto, 1900).

One of the most important of all arrangements and agreements affecting Canadian defence which have come into force since 1814 is what is known as the "Rush-Bagot Convention."

Under this Convention, entered into on behalf of America and Great Britain in April, 1817, by Mr. Richard Rush, Acting Secretary of State for the United States, and Sir Charles Bagot, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of Great Britain, it was agreed that the naval forces maintained by the United States and Great Britain on the great lakes were to be confined to the following number and description of vessel on each side:

Each of these vessels not to exceed 100 tons burthen, and its armament not to be heavier than one 18-pounder cannon.On Lake Ontario, one vessel.On the upper lakes, two vessels.On Lake Champlain, one vessel.

All armed vessels on the lakes, beyond what is here authorized, were to be forthwith dismantled, and no other vessels of war were to be built or armed upon them. The naval force so limited was to be restricted to such services as would in not respect interfere with the proper duties of the armed vessels of the other party.

The Convention to be terminable after six months' notice by either side.

This Convention amounts, in its spirit, to partial and mutual disarmament on the lakes, the vessels authorized being sufficient for protection and revenue purposes only. It has been continuously in force to the present day, and has worked in the interests of peace.

In its limitations with respect to tonnage and armament of vessels it may, perhaps, want some revision to suit modern changes;1 but if so, there should apparently be little difficulty in carrying this out by mutual agreement.

As a matter of fact, it has been, if not loosely, at all events most liberally interpreted already, and what seems required is that under any alterations its spirit should be adhered to. This, it may be assumed, was not only to avoid as far as possible friction and rivalry between vessels and their crews under the two flags on these lakes, but also to insure that the armed strength of the flotilla, which, from being available in either their ports or on their waters, could at any moment be placed upon the latter, should give no undue ascendancy to either nation.

The abrogation of this convention has been at times suggested, and action in this direction would no doubt be welcomed1 by those shipbuilding firms upon the lakes who from their locality find themselves under the treaty shut out from contracts for the construction of gunboats and war-vessels; but it would probably be a political blunder to terminate it, and one which would ultimately cause serious expense to both nations in land fortifications and armaments.

What has aroused remonstrance in Canada at times, both against the Dominion and the Home Governments, has been the permission given by them on more than one occasion for warships borne on the strength of the United States Navynot, it is true, built upon the lakes, nor for service upon them, but for use as training-ships for the Naval Militia of States of the Union1—to pass up from the sea unarmed to stations on the lake shores, their armament for such training being sent separately, by rail or otherwise, to those posts, thus keeping within the letter, while, in the opinion of some, evading the purpose, of the Convention.

It appears that the Hawk and the Dorothea were so permitted. Also, in 1907, the gunboat Sandoval passed up through the Canadian canals to Charlotte, on Lake Ontario; and the Nashville also, in 1908, receiving her armament at Buffalo, on the Buffalo River, at the head of the Niagara River, near the exit of Lake Erie.

Those American armed vessels, also, serving on the lakes under the Convention are stated to have become in recent years more powerful than those flying the British flag.

But how this may be at the present moment is, of course, a matter perfectly evident to all upon the lakes, and whatever has taken place under the Convention has been recognized by the Home Government and Dominion Government, in concert with that of the United States.

It also is to be assumed that in equity it is perfectly open to Canada to establish her own training-ships for her own Naval Militia on the lakes, in the same manner as America has done, whenever she may desire and determine to do so.

If Canada is to maintain a navy of her own for the protection of her lake frontier, such a step becomes in the future essential; and with regard to this, the writer of the prize essay1 offered by the Navy League of Canada for the best paper on "Shall Canada have a Navy of her Own?" reflected doubtless the feeling of the Dominion When she said: "In establishing training stations it seems desirable to bring them to the people to localize them. We may therefore, perhaps, besides establishing such stations in or near some of our Atlantic and Pacific ports, follow the lead of our neighbours, who do not look upon training naval stations in ports of the great lakes as contrary to existing treaty provisions."

The United States, apart from what that lead has given them, have advantages in the size and resources of their large cities and ports bordering the Great Lakes, which should make it impossible for them to misconstrue any action Canada might take towards training her own seamen on her own lake shares. Among these ports we need only mention Chicago, Milwaukee, and Manitowoc, on or near Lake Michigan; Bay City, on Lake Huron, with Sandusky, Cleveland, Erie, and Buffalo, on or near Lake Erie,2 though there are others on these, and on the remaining lakes.

Of recent years, along the American shore or the lakes, there has been a wave of enthusiasm in the direction of forming Volunteer Naval Brigades, and from this source many volunteers came, it is said, during the late war with Spain. Naval Militia organizations were established also at Chicago, Detroit, Toledo, and Cleveland.

An article in the Chicago Tribune of January 30, 1898, enters largely into what had been accomplished in that respect up to twelve years ago; and although it is not an official paper, it evinces a knowledge of details1 which makes it well worth perusing.

The arrangements then made are said to provide for the rapid conversion, into fighting vessels for lake service, of suitable steamers and merchant ships, as well as for their manning and armament, so that over 200 specially selected steamers could be quickly placed upon the upper lakes; also some thousands of officers and men from the National Guard and Naval Reserves of Illinois, and any number of rapid-firing guns, adapted to this service, from the arsenal at Washington.

The article deals with the defence of Chicago against an attack from the Canadian border through the Straits of Mackinac into Lake Michigan, and illustrates what measures the United States have, in the undoubted exercise of their rights, taken to protect their own shores.

One must, however, recognize that the organization and resources which provide for the defence of Chicago would assist also to secure the passage of the Straits of Mackinac2 into Lake Huron, and transport troops to the Canadian shore. This affects materially the defence of Canada; and should armed vessels be able to force an entry from Lake Huron into Lake Erie, they could there be met by vessels from Buffalo, Cleveland,1 etc.

The obligations which, with the creation of a Canadian Navy, must devolve largely upon that navy—obligations due to the Canadian people and cities on the Atlantic and Pacific seaboards, and on the Canadian shores of the lakes, as well as to the general cause of Imperial defence—are exactly those which the United States owe, and have shown that they are alive to, with respect to their own people and their own cities, such as Chicago.

The conclusion seems to be that Canada must follow the example of the United States, and establish a Naval Militia, or its equivalent, at such stations as will afford convenient opportunities for the training of the officers and men who are to form it.

Such a movement would also encourage the development of the Canadian shipbuilding industry, which, although it had been comparatively dormant for a long period, is now reviving.

In 1907 no large iron or steam vessels had been built on the St. Lawrence or on the Atlantic coast of Canada,2 but there are now steel works at St. John (New Brunswick), at Sydney in Cape Breton, and at other places; while on the Canadian shores of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, of the St. Lawrence, and of the lakes, there are excellent ports, at some of which dockyards and shipyards now exist, or where, if not existing or of insufficient size, they could be readily constructed. Many varied considerations enter necessarily into the questions of what constitutes a suitable naval port adaptable to the requirements of war; and where it is most desirable that shipbuilding and refitting facilities should be developed. Only experts can pronounce advisedly as to this; but, at all events, there is in Canada no want of good harbours.

We may mention Quebec, Montreal, Halifax, St. John, Gaspé, Sydney, Esquimalt, Prince Rupert, Vancouver, Collingwood, and Midland (both on the Georgian Bay, Lake Huron),1 and Kingston.

Very large steam vessels have been recently turned out from Canadian yards,2 and freight traffic upon the upper lakes, and along the St. Lawrence to Montreal, is increasing enormously. It is a striking fact that the wheat shipments in vessels from Montreal in 1908 (nearly 28,000,000 tons) was one-third more than in 1907, and double that of 1906, the great bulk of this being Canadian grown wheat. In this year also about 100,000 cattle were shipped.

The growth in number of Canadian vessels plying the waters of the great lakes has recently excited considerable comment in reports upon lake navigation. In 1874 the registry of Canadian tonnage on the lakes comprised 815 vessels, of a total gross tonnage of 113,008 tons. On December 31, 1908, the total number of Canadian owned vessels plying on the lakes (although some were registered elsewhere) is said to have been 2,070, of a gross tonnage of 265,133 tons, and it is steadily increasing.

The stream of vessels (under different flags) passing through that portion of the Upper St. Lawrence termed the Detroit River is constant. It represented in 1909 the passage of a vessel about every fourteen one-fifth minutes, and of 218 tons of freight per minute of the twenty-four hours.

Very interesting particulars regarding the ports on both shores of the great lakes, and the rapid development of shipping and commerce upon the waters of the St. Lawrence route, are to be found in the various official reports on these subjects.1 Here we cannot enter at length into them, but only touch briefly upon the facilities of some among several of the Canadian lake ports in Appendix III.

Fleets of steamers run upon these lakes and on the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in connection with the great Canadian transcontinental railways, and there seems no reason why Canada should not in a few years, from her maritime resources and population, organize a powerful auxiliary volunteer fleet.

One great change since 1874 affecting naval defence in Canada, as well as elsewhere, has been, of course, the supersession of sailing vessels by steamers, and the general

Introduction of Steam and Electricity

In the future, the operations of war will move faster than in the past, and the control of the lakes will possibly be decided in days, if not hours, instead of in months or years.

The time when fleets manœuvred for weeks, as did those of Yeo and Chauncey, on Lake Ontario, seeking for the weather gauge, or some advantage from the wind, will not recur; and the co-operation between fleets and between naval and military forces, through steam, and the telegraph both wireless and in other forms, can be carried out with greater certainty than was possible a century ago. The progress of science in this direction alone— not to speak here of aeroplanes and balloons—will favour prompt concentration for either defence or attack, and also make more easy and more rapid the landing of troops upon an enemy's shores.

Another important change bearing upon defence which has taken place since 1814, and which is connected with the great lakes, has been the construction of

Canals,

These complete the through water communication to the Atlantic, and some of the earlier were undertaken as the result of the experience of the war of 1812–14.

Very large sums of money indeed—about 80,000,000 pounds sterling—have been spent upon the construction, deepening, and maintenance of the Canadian canals, which are of much importance to the Dominion in both a commercial and a military sense.

The River St. Lawrence,1 with the canals established along its course, now affords communication by water for vessels under 14 feet draught between Lake Superior and Montreal, where ocean navigation commences. The width of these canals varies from about 144 to 164 feet, the locks, forty-eight in number, being designed to accommodate vessels of 255 feet in length, with 44 feet beam. When originally constructed, their depth averaged about 10 feet only; this is now being increased throughout from 14 feet to 22 feet, while in many other respects they have been improved.

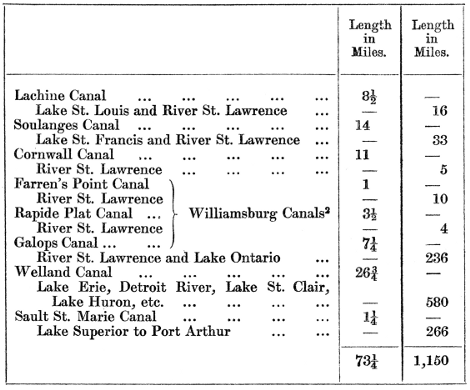

The following table2 shows the St. Lawrence water route from Montreal to Port Arthur, on Lake Superior, the length of the various stretches of canal along it having for convenience been placed in a column separate from that giving the length of the lake and river portions. From this can be seen at a glance the extent of narrow canal to be protected in war.1

The canal approaches are well defined, lighted with gas-buoys, and admit of safe navigation, under competent pilots, by day or night; and the Sault St. Marie, Welland, Cornwall, Soulanges, and Lachine canals are electrically lighted and operated.

It is of interest to say a few words about each of these St. Lawrence canals, taking them in order.

The Lachine, from Montreal to Lachine, turns the St. Louis or Lachine Rapids above Montreal. It was voted, for military purposes mainly, in 1815, begun in 1821, and opened in 1825.

The Soulanges turns the Cascade, Cedar, and Coteau Rapids. It has superseded the old Beauharnais Canal.

The Cornwall was begun in 1832, and finished in 1843. It turns the Longue Sault Rapids above Cornwall.

The Williamsburg canals (Farren's Point, Rapide Plat, and Galops) turn a series of rapids between the Longue Sault and Lake Ontario. Descending vessels, however, often run these.

The Welland Canal, between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, turns the Falls of Niagara. This canal is also important for military purposes, though it is close to the frontier. It was projected by Mr. William Hamilton Merritt, who served actively in the war of 1812–14, and the Duke of Wellington encouraged the enterprise by taking several shares in it. It was begun in 1825, and completed about 1841.

Between this canal and the Sault St. Marie Canal, connecting Lakes Huron and Superior, there is deep water communication for very large vessels. The Sault St. Marie Canal was begun only in 1889, the object being mainly to avoid the payment of duties to the adjoining American canal, and complete an "all red" route from the head of the great lakes to the sea. It is cut through St. Mary's Island, on the north side of the Sault St. Marie Rapids, in the St. Mary's.River.

A reference to the map facing the concluding page will show the immense advantage it will be, in a commercial as well as military sense, to Canada to deepen the canal system and water-channels, so that the largest ocean-going vessels can pass through from Lake Superior to the Atlantic, and vice versa1

At present vessels of 10,000 tons and upwards are employed to carry ocean freight from the western lake ports to Buffalo, at the head of the Niagara River (in the United States); but, owing to the insufficient depth of the Welland and other canals lower than this point, much of the freight is here transferred, and conveyed through the United States (either by American railways or by the Erie Canal, which is being enlarged, and the Hudson River) to New York, as the best route to the ocean. Three-fourths, perhaps, of the large grain and other traffic of the West formerly found its way thus to the sea through United States and not Canadian territory.

Could this traffic, without breaking bulk, be taken through to Montreal and the ocean, the distance to tidal water Would be about as short, while the route would lie throughout over Canadian water, and the cost, it is said, be little more than one-half.

But the St. Lawrence canals form by no means all the canals of Canada. In addition to these we must mention also the following, among others of less prominence:

The Rideau Canal.—This was constructed by Great Britain, chiefly for military purposes, at the instance of the Duke of Wellington, the want of it having been much felt in the war of 1812–14. Its object was to connect Ottawa, the present capital of the Dominion, with Kingston, on Lake Ontario (about 126 miles), by a water route north of the frontier, and available for the conveyance of troops and stores. It was commenced in 1812, carried out under Colonel By,1 R.E., and finished in 1832. Its depth does not exceed 9 feet.

Montreal also now communicates with Kingston through the Lachine Canal, the Ottawa River, with its canals, and the Rideau Canal.

The Richelieu and Lake Champlain Canal system commences at Sorel, at the confluence of the Richelieu and St. Lawrence below Montreal, and affords communication via the River Richelieu with Lake Champlain, a distance of eighty-one miles to the American frontier north of the lake.

The average canal depth is about 7 feet. This canal was also suggested by the experience of the war of 1812–14. It was begun in 1830, and completed in 1843.

In American territory south of Lake Champlain there is communication by American canal with Albany, on the Hudson.

The Trent Canal was in 1907 open as far as Lake Simcoe. It is intended to connect Lake Ontario, from a point near Kingston, with Lake Huron—200 miles—via the River Trent, various lakes (including Lake Simcoe), and the River Severn. The actual canal distance is short (about twenty miles). It has a depth of about 6 feet only, but in war would be useful for the conveyance of troops and stores.

When it is understood that from these main canals run also subsidiary branches, too many to be here enumerated, it can be seen what a considerable part they play in the communications of Canada.

A further projected canal, not as yet begun, but which has been practically approved and its route fully surveyed, must be specially mentioned. This is the Georgian Bay Canal, which it is calculated will take ten years or so to complete, at a cost of about 2,000,000 pounds sterling a year throughout that period. Commercially it will be of great importance, its object being to connect Montreal—i.e., ocean navigation—with the northern end of Lake Huron (the Georgian Bay) via the River Ottawa and Lake Nipissing. The total distance is about 440 miles, but of this the greater part will consist of rivers and small lakes, not of canal; and the route will provide a water passage between Lake Superior and the Atlantic, in addition to that by the St. Lawrence and through Lakes Erie and Ontario. The depth is to be not less than 22 feet throughout to Montreal, which will accommodate the large lake vessels of about 600 feet in length, 60-inch beam, and usually with a draught of some 20 feet.

The distance from Port Arthur, on Lake Superior, through this canal, to Montreal, the head of ocean navigation, will be 934 miles, and materially less than that by any other route.

At present, by the St. Lawrence route to Montreal, it is about 1,216 miles; and by Lake Erie, Buffalo, and the United States to the Atlantic, it is more.

From Port Arthur to Liverpool by this canal will be about 4,123 miles. It is now, via New York, about 4,929 miles.

It will bring the shores of the Georgian Bay within seventy hours of Montreal, but the determination to construct it is not founded especially on the time which will be saved in transit through it, for the greater speed which can be kept up on the St. Lawrence route, when on the open water of the lakes, much reduces any advantage on this head.

The point, perhaps, most strikingly illustrated by the resolution to build it is the pressing importance of the increasing traffic between Western and Eastern Canada, and between both and Europe, which it is considered will find ample employment for more than the other existing or projected channels of communication, by water (including that via Hudson Bay and Straits), as well as by rail.

This canal is expected to be free from ice from about May to November.

The advantage it would be in a military sense is very obvious, affording as it would a secure route in war well to the north of Lakes Erie and Ontario, running through Canadian territory, and connecting Montreal and the sea with Lake Huron.

The Canals which we have enumerated above have certainly contributed greatly, since 1814, to improve the military communications throughout Canada, and in this sense facilitate Canadian defence; but, on the other hand, it must never be overlooked that, in order to reap the advantages which they confer, they must in war be very carefully watched and protected.

They are in some instances particularly open to raids; and this necessitates the defence of a considerable length of canal by land forces, because war vessels alone upon the rivers and lakes adjoining them, even if in the ascendant on those waters, cannot be relied upon to keep them open.

Another change since the war of 1812–14 bearing very vitally upon Canadian defence has been the construction of

Railways,

Under the conditions which prevailed during that war, and when the Duke of Wellington wrote his letter to Sir George Murray, on December 22, 1814,1 the theatre of war to be considered in relation to the operations upon Canadian territory of armies accompanied by artillery and heavy transport for supplies was practically limited on the north to the northern fringe of the great lakes, and to the west and east did not extend beyond Lake Huron and Montreal (or Quebec), the country beyond these limits being, as we have before said, difficult of access, and the land communications for an army very bad.1

Now, this is not only changed, but is becoming so rapidly and increasingly altered day by day with the opening up of the country, that in writing upon Canadian defence it is absolutely necessary to consider not simply what exists now, but what is almost certain to come within the next very few years, in some cases even within a year or two years.2

What was trackless wilderness in 1814 is now covered with railways, which traverse both Canada, and the United States close to her frontier, in many directions, connecting all the chief cities and towns, and linking by more than one railway line the Atlantic and Pacific Seas.

Most probably in the next war Canada will have to defend territory northward to Hudson Bay and westward to the Pacific Ocean.

To this we shall again advert farther on, but first of all must mention the most important of the railways which now traverse Canada, some running east and west, nearly parallel to the frontier, and others from various points along that frontier in a northerly direction.

It will indicate what a great change has been created by the construction of railways since the war of 1812–14 to say that if anyone standing at a central point—say Toronto (formerly York)—could survey the entire country around, he would see railways running to all points of the compass.

For instance, to the north and north-west, towards the Georgian Bay {through which district it was so difficult to supply Mackinac in the war); to other points on Lake Huron; and to Lake Nipissing.

To the south-west, towards Amherstburg and Detroit (the scene of Brock's success in 1812); and along the Thames (the line of Proctor's retreat in 1813).

To the south, towards Lake Erie and the Niagara district (where, from bad roads and failure of food and necessaries, Barclay and De Rottenburg endured so much in 1813).

And to the north-east—bordering Lake Ontario—towards Kingston and Montreal (to which points in the war the only main road became at times impracticable for heavy transport).

He would see now in these directions a complete network of railways, uniting, often by more than one line, the main cities and towns, such as Montreal, Kingston, Hamilton, and very many others, crossing also the St. Lawrence (under its various names of St. Lawrence, Niagara, and Detroit, etc.) at more than one point, and connecting, beyond the Canadian boundary, with the railways of the United States, which to the southern side of the frontier come down also in all directions to the towns on the southern fringe of the lakes and the St. Lawrence.

It is much the same thing with the country south of Montreal bordering Lake Champlain.

Also, to the north of the old theatre of war, and far outside its limits, important transcontinental lines now entirely cross Canada, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, carried, with much labour and at a great expense, over the passes of the Rocky Mountains.

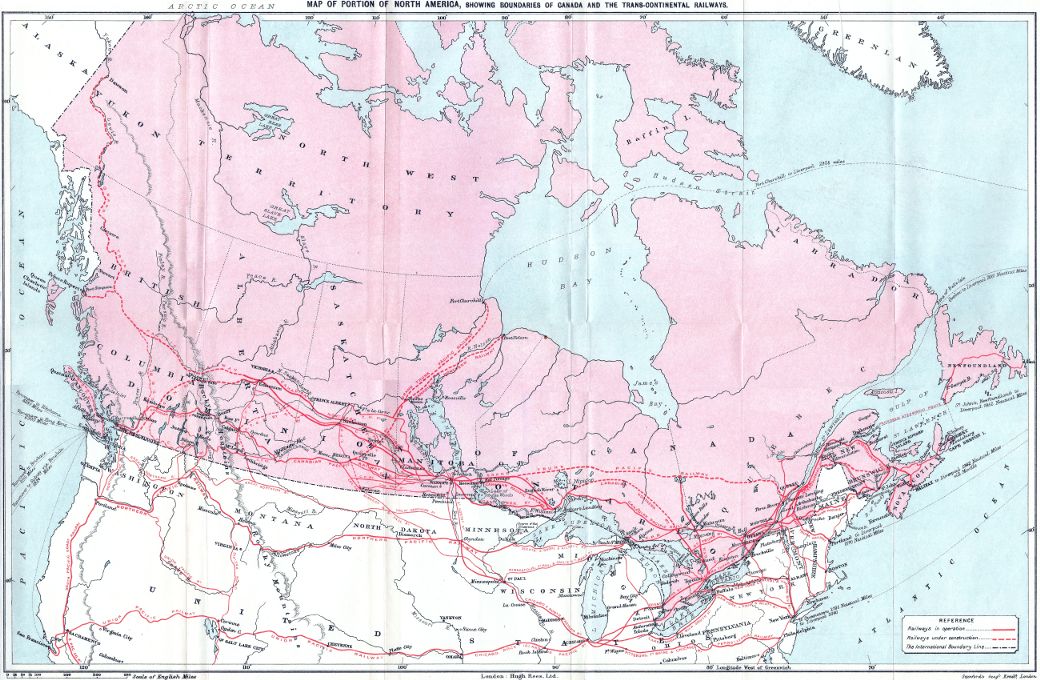

Without attempting to allude to all the railways which together make up the nearly 30,000 miles of line throughout the Canadian Dominion,1 we may give a sufficient idea of these by referring to the live chief railways (which have now absorbed into their system many of the others).

These five railways are the Intercolonial, the Grand Trunk, the Canadian Pacific, the Grand Trunk Pacific, which is part of the Grand Trunk system, and the Canadian Northern.2 See map facing p. 134.

These are all either in full operation, partial operation, or just on the eve of completion.

The Intercolonial Railway

The line was run entirely through Canadian territory, and as far as possible to the east of the American frontier. From Halifax—and also from St. John and Sydney—it passes to Moncton, thence by the Bay of Chaleur, and round close to the St. Lawrence, through Rivière de Loup, to Quebec and Montreal, where it connects with various other Dominion lines.

The Canadian Government is, it is said, about to spend a considerable sum of money upon Gaspé Harbour, at the mouth of the St. Lawrence, as a port, to be used in connection with a new line of fast steamers to Liverpool. This will form the shortest route from Canada to Liverpool.

The Grand Trunk Railway

It connects the provinces of Quebec and Ontario, at various points of the Canadian frontier, with the railway lines of the United States, thus communicating with all the chief cities of the Union.

It links Quebec, Montreal, Kingston, Toronto, Hamilton, and the Niagara frontier with each other.

From Toronto it runs north towards the Georgian Bay and Lake Nipissing, and west to Port Sarnia at the southern end of Lake Huron, continuing on to Detroit and Chicago in the United States.

From Montreal it runs south-east to the American Atlantic port of Portland; south to La Colle, joining with the Central Vermont Railway, which skirts Lake Champlain and passes on to Albany and New York; to the west it runs to Ottawa and the Georgian Bay.

It also connects with the Intercolonial Railway and the maritime provinces, by the Atlantic, Quebec and Western Railway.

The Canadian Pacific Railway.

This is a very important railway strategically both for Canada1 and the Empire.

It was opened in 1886, having been promoted largely by a few far-seeing men, among whom were Sir John Macdonald, Premier of Canada; Sir George Stephen, now Lord Mountstephen; and Sir Donald Smith, now Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal. It opened a way through Canadian territory to the Pacific, and to the mineral and agricultural resources of the Far West,1 and links with its steamship lines on the Atlantic and Pacific, by an entirely British service, Great Britain, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, India, Japan, and China.

Its through and branch lines run to Quebec, Montreal, Toronto, St. John (New Brunswick), Halifax, and many other important points of the Dominion, and on to the United States; but in respect to defence, its chief feature is the through trans-continental route from ocean to ocean. By this the transit from Quebec to the Pacific port of Vancouver, some 3,000 miles, is effected within about five days; while the distance from Liverpool to various points in China, Japan, and on the Pacific coast, has been reduced by from 1,000 to 1,200 miles.

Yokohama is brought within a little over 10,000 miles of Liverpool, as compared with over 11,000 miles from Plymouth (the nearest point in England), via the Suez Canal.

It runs, however, at certain places, and for some distance along portions of its route, especially to the west of Lake Superior, close to the American frontier.

In connection with the Canadian Pacific Railway the New Zealand Shipping Company has just established a line of steamers for cargo only from Eastern Canadian ports to Melbourne, Sydney, Auckland, Wellington, Lyttelton, and Dunedin.

The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway,

This line, in a defensive sense, has a special value. It will form an all-British line of about 3,600 miles, from Moncton, in New Brunswick, by Quebec, and well to the north of Lake Nipigon and the great lakes, to Winnipeg, and thence by Edmonton and the Yellowhead Pass1 to Prince Rupert, in British Columbia, a very line land-locked harbour on the Pacific Coast, north of Vancouver Island.

This will still further shorten the distance from London to Yokohama, in comparison with any other route, by some 200 miles. From Moncton a branch line will run to St. John; and Halifax will be reached by the Intercolonial Railway.

Branch lines will also be run from the main route, southerly to Fort William, and Port Arthur on Lake Superior); towards the Georgian Bay, connecting with the Grand Trunk line; and also to Montreal.

This railway, moreover, reserves power to construct, if desired, several other branch lines, of which we may mention the following: One from a point between Winnipeg and Edmonton, northward, to the shores of Hudson Bay, in the vicinity of Fort Churchill; one from a point between Edmonton and Prince Rupert, southward to Vancouver and northward to Dawson, on the Yukon; and others to Regina and Calgary. A steamship line in connection with this railway is to run between Prince Rupert, Vancouver, Victoria, and the islands on the coast of British Columbia.

The Canadian Northern Railway.

This line, now in construction, connects Port Arthur, at the head of Lake Superior, with Winnipeg and Edmonton, and is being pushed through the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific.1 It has also sections west of Winnipeg, opening out the country towards Prince Albert and Regina. Eastward from Winnipeg it will connect with Port Arthur the Georgian Bay and Toronto. It has many miles constructed in the province of Quebec; and, in the direction of Hudson Bay, a portion has been already completed as far as the Pas Mission (100 miles), running from a point west of Lake Winnipeg, along the valley of the Nelson River towards Port Nelson2 Before long it will doubtless reach Hudson Bay, and contribute to the opening up of the valuable grain and pasture districts of the Saskatchewan and Peace Rivers.

What the completed line to Hudson Bay will accomplish is thus alluded to in Stanford's Compendium of Geography and Travel:

"Churchill Harbour is situated near the centre of the North American continent—i.e., halfway to the Pacific—and yet, owing to the convergence of the meridians towards the north, it is actually nearer to Liverpool than either Montreal or New York. The distance from Churchill Harbour to Liverpool, via Hudson Straits, is about 2,926 miles; from Montreal, via Cape Race, it is 2,990; and from New York, via Cape Clear,1 3,040 miles, showing 64 miles in favour of Churchill as compared with Montreal, and 114 miles as compared with New York. Churchill Harbour is only 400 miles from the edge of the greatest wheat-fields in the world."2

In connection with the Great Northern Railway, a line (the Royal Line) of large and fast steamers has just been opened by two twin vessels, the Royal Edward and Royal George, to run between Bristol, Quebec, and Montreal in the summer, and probably Bristol and Halifax in the winter.

The above railways may in war be found of far-reaching importance to the Empire and to Canada. Until the Canadian Pacific was built, it would have been almost impossible to have concentrated troops or supplies required for the defence of the frontier west of the Mississippi; or reinforced, from Canada, posts on the Pacific coast, such as Esquimalt, which has recently been taken over by the Dominion for the Home Government.

Imperial interests in the Pacific Ocean are now likely to become greater year by year. The rise of Japan, the projected Panama Canal, with the situation of New Zealand and Australia, all point to this; and the trans-continental lines which now bring the Pacific shore and the food-supplies of the West within almost ten days of England are strategically of great value. They would also facilitate the occupation of a second or third line of defence north of the great lakes.

But while speaking of railways it must be said also that those to the south of the Canadian frontier, of which there are many, would facilitate an enemy's concentration for attack, just as those to the north of it would facilitate Canadian defense; and that the defensive value of the Dominion railways depends much upon their direction with respect to the frontier, their vicinity to it, and the power of protecting them.

If from their position they can be easily and rapidly reached, they are liable to be cut, or perhaps seized and utilized, by an enemy.

Those railways farthest from the frontier are from their situation necessarily the most secure.

We have said that Canada will in the next war have probably to defend territory northward to Hudson Bay and westward to the Pacific Ocean. Already it is clear that many important cities between Lake Superior and the Pacific, and also ports on that sea, such as Vancouver, Esquimalt, and Prince Rupert, must be defended, and this part of the Dominion may be regarded as forming a separate section of defence from that between Lake Superior and the Atlantic.

With respect more particularly to Hudson Bay, it may seem, perhaps, to some unnecessary, even absurd, to consider this district, not as yet opened up, from the point of view of defence. Part of it is most difficult to traverse, but, nevertheless, Hudson Bay is not, from its southern shore James Bay), more than 500 miles from Montreal, or Ottawa, or Toronto, and less from Lakes Superior and Huron. When we reflect that railways will pretty certainly soon reach that bay at more than one point;1 that across its waters an increasing commerce will in the future be borne in the open season eastward to Great Britain and Europe; that its distance from the great lakes is little more than from Berwick to Land's End, in England, and not nearly as far as from Cape Town to Pretoria, in South Africa, it seems no wild speculation that in the next war, were Hudson Straits not made secure, an enemy's naval and military force might pass through, dominate the bay, and strike at Canada from the north.

Everything seems to point to the conclusion that Canada is not commencing to build her navy before her interests on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts and on her inland waters absolutely require the protection of such a navy as well as of the Navy of Great Britain; and, further, that for her southern frontier she wants an efficient and numerically strong land force.

Another point in which a change which bears upon defensive arrangements has taken place in Canada since 1814 is the

Increased Importance of Cities and Towns

The great consequence it is to Canada that preparations should be made to ensure their defence is undoubted. If its be thought that, if left undefended, they will not in modern war be bombarded or injured, it must not be overlooked that they will then, at all events, be almost certainly occupied, with the disastrous consequences, in a military and financial sense, which this must entail.

Years ago, before the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, the Canada Defence Act provided for the guaranteed loan of 1,000,000 pounds sterling for the building of forts round Montreal, and for a free gift for the armament of those forts, and of others at Quebec and Levis opposite. This was apparently declined by the Dominion Government,1 in favour of a transfer of this guaranteed loan of £1,000,000 to the Canadian Pacific Railway.

This, as has before been said, was a measure which time has entirely vindicated; but the original provision of this loan indicates the military consequence attached at that period to the defence of these points, and which nothing has since occurred to materially after. The Dominion now practically possesses more than one Trans-Continental Railway, and the following considerations, therefore, seem those which at the present moment more immediately require to be weighed.

I. That, if in war, through want of adequate preparation to maintain them, the posts of Quebec, Montreal, or Kingston were to fall to an enemy, the benefit of previous expenditure in other directions upon defensive measures might be largely, if not entirely, neutralized.

II. That Canada would suffer a greater disaster than at any time befell her in the war of 1812–14; and

III. That both British and foreign critics of other nations upon the operations of that war accept this, in addition to the importance of the command of the lakes, as among the main lessons of that contest.2

What is meditated for the future in connection with the defence of Canadian cities an posts is known to and rests with the Dominion authorities. We merely allude here to the importance of these posts in relation to Canadian defence.

Finally, among the changes affecting defence which have taken place since 1812–14, one—viz. the change in the character of

Modern Weapons and Warfare

But among changing systems, one point remains unaltered, which is that guns, whether naval, garrison, field, or horse, to be of full value, must not be such as are partially obsolete, or liable to be outclassed by the artillery to which they may be opposed,1 and which, from a distance, can put them out of action with but little risk of damage to themselves. Defence to be thoroughly effective must be up-to-date.

In conclusion, it is only the system, not the necessity of the defence of posts, which has changed.

1 It is stated that the existence even of the Rocky Mountains, or, as they were then termed, the "Stony Mountains," was then only known as a matter of vague report.

2 The boundary line in Passamaquoddy Bay from the mouth of the St. Croix to the Bay of Fundy has only recently been settled by treaty ratified at Washington, August 20, 1910.

1 See Alison's History of Europe: Continuation, 1815 to 1852, vol. vi. (1865).

2 Some interesting particulars with respect to the award of Rouse's Point to the United States, taken from Lake George and Lake Champlain, by W. Max Reid (New York, 1910), are given in Appendix II. This post was subsequently strongly fortified.

1 For instance, the 18-pounder gun is now out of date.

1 And more and more so as communication by the St. Lawrence and canals to the ocean becomes further deepened and available for larger war-vessels.

1 The militia is a State, not a Federal, matter in the American Union.

1 Mrs, W. Hews Oliphant, of Toronto. This essay was published on April 16, 1909.

2 And dredging and other operations for the improvement of these ports are constantly going on. See Annual Report of the Lake Carriers' Association, p. 1909 (Detroit, 1910). The Port of Erie is, in effect, the Presqu'ile of 1812–14.

1 As these are of interest, the article is given nearly in extenso in Appendix I. Attention was at this period naturally directed to the matters dealt with, as 1898 was the year of the Spanish-American War.

2 The Post of Mackinac, which commands these Straits, was restored to the United States in 1814 (see p. 91).

1 See The Military; Aspect of Canada, by Lieutenant-Colonel (now Major-General) T. B. Strange, R.A., Dominion Inspector of Artillery, delivered at the Royal United Service Institution, May 2, 1879.

2 Canada's Resources and Possibilities, by J. S. Jeans (1904); The Canadian Annual Review (1907); House of Commons Debates (Ottawa); and other sources.

1 Important, in a defensive sense, from their position on this lake. It was in Matchedash Bay that it was contemplated in 1814 to establish a naval port had the war gone on.

2 One built recently at Collingwood, for instance, for the Northern Navigation Company has a length of 365 feet, carries 400 first-class and 70 second-class passengers, with over 3,000 tons of freight; but her draught of 27 feet at present precludes her from passing through the Welland Canal, between Lakes Erie and Ontario.

1 Such as the Port Directory of Principal Canadian Ports and Harbours; Department of Marine and Fisheries, Ottawa, August, 1909. Reports of Harbour Commissioners and Port-Wardens; Department of Marine and Fisheries, Ottawa, 1909. Annual Report of the Lake Carriers' Association for 1909, Detroit, U.S. (1910). Great Lakes Port Facilities (reprint of Hydrographic Information); Washington, D.C., March 24, 1910. And Statistical Report of Lake Commerce passing through Canals at Sault St. Marie, Michigan, and Ontario during season of 1909; compiled from official records.

1 Under its various names, see p, 26.

2 From the Annual Report of the Department of Railways and Canals

Ottawa, 1909); also from Canada: An Encyclopedia ("Her Waterways"), by Castell Hopkins.

1 See map facing p. 124.

2 The Farren's Point, Rapide Plat, and Galops Canals, taken together, are often termed the "Williamsburg Canal System."

1 The largest vessels constructed and plying on the upper lakes

cannot now pass further eastward than the eastern point of Lake Erie.

1Hence the old name of Ottawa, which was "Bytown."

1 Nevertheless, in the summer of 1814 a small party of about

600 Canadians with one gun succeeded in moving from Mackinac

to Prairie du Chien, on the Mississippi, 250 miles, capturing a fortified

post there; but this does not affect the fact that the serious conflict

between the main armies was limited to the smaller area.

2 The rate of progress in certain places of railway construction is

astonishing. On the prairie section of the Canadian Pacific Railway

six miles of new line were sometimes laid in one day.

1 The railway mileage of Canada is per head of her population greater

than that of any other country in the world.

2 For several of the details as to these railways we are indebted to

"The Railway Development of Canada" by Dr. George R. Parkin,

C.M.G. (Scottish Geographical Magazine, May, 1909), and also to Imperial

Outposts, by Colonel (now Major-General) A. M. Murray (1907), and the

Gates of Our Empire, by T. Miller-Maguire, M.A., LL.D. (1910).

1 Incorporated with Nova Scotia.

2 It has practically absorbed the Northern Railway, begun in 1850,

and the Great Western, commenced about 1853.

1 The extent also commercially of the operations of this line may be

gathered from the statement of its president, Sir Thomas Shaughnessy,

at the annual meeting of 1908, that throughout the last six years the

rolling-stock had been increased at the rate of one locomotive (i.e.,

engine) every three working days, one passenger car every two, and

fourteen freight cars every day, and was still behind what was required

to cope with the traffic.

1 Before its construction this traffic all passed virtually by the

American trans-continental lines.

1 The most favourable spot to cross the Rocky Mountain range to be

found at any point of it. Recently difficulties, connected with labour-supply, have made it probable that the line cannot be carried through

the mountains as early as the close of 1911.

1 Through the Yellowhead Pass to New Westminster and Vancouver,

and ultimately to Quatsino, north point of Vancouver Island.

2 It is understood also that the construction, by an independent

syndicate, of a line to Fort Churchill has been arranged.

1 South point of Ireland. By other routes taken, the distance is

rather greater.

2 "Of what consequence this route may become, is realized by the

consideration that from Liverpool to Winnipeg it will save inland

carriage of about 2,000 miles, as compared with the route via New

York or Halifax. It would reduce the distance from Liverpool to

Japan to 9,734 miles—i.e., to a distance of 2,352 miles less than that

via New York and San Francisco, which is 12,078 miles. Professor

Hind, of Canada, considered in 1878 that, with strongly-built steamers,

using the magneto-electric light, Hudson Straits could be navigated

from June to October inclusive."—See Stanford's Compendium of

Geography and Travel, p. 317.

1 A few years ago it was contemplated to run a railway north from Toronto to James Bay on Hudson Bay, and through apparently this has not as yet been determined on, it is more than probable that before very long the silver and mineral districts lying between the Georgian Bay and Hudson Bay will be traversed by rail.

1 The Canadian forts and fortifications of 1812–14 are necessarily, where they still exist, no longer formidable as defensive works.

1 Lecture on "The Military Aspect of Canada," by Lieutenant-Colonel (now Major-General) T. B. Strange, R. S. Dominion Inspector of Artillery, delivered at the Royal United Service Institution, May 2, 1879.

1During the late South African War, in the operations before Ladysmith, this was forcibly illustrated.

- Previous: Chapter V

- Next: Chapter VII

- Up: Canada and Canadian Defence

![Homepage [Logo]](/images/logo.png)

![[Public Domain mark]](http://i.creativecommons.org/p/mark/1.0/88x31.png)